‘In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth, and the earth was without form and void’National Cathedral program considers spiritual dimension of exploration and Apollo 8’s unifying missionPosted Dec 12, 2018 |

|

[Episcopal News Service – Washington, D.C.] In the heyday of America’s space program, the Apollo 8 mission that went aloft 50 years ago this month was a first in all of human exploration, not just that of space.

Humans left Earth’s orbit for the first time and headed to the moon nearly a quarter-million miles away. Just shy of three days later, on Christmas Eve 1968, William A. Anders, Frank Borman and James A. Lovell Jr. put their spacecraft into lunar orbit and became the first people to see the far side of the moon. Later that day, they became the first to see the Earth rise over the lunar horizon.

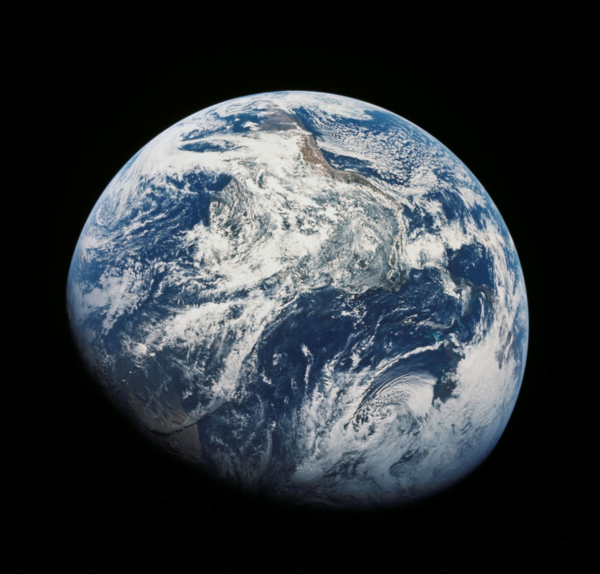

“Look at that picture over there! Here’s the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty!” astronaut William A. Anders said on Dec. 24, 1968, as he, Frank Borman and James A. Lovell Jr. rode the Apollo 8 space capsule through their fourth orbit of the moon. “The hair kind of went up on the back of my neck,” he later recalled. Anders grabbed a Hasselblad camera and snapped one of the most iconic images of the Space Age. As Anders saw it, the Earth “rose” from the moon’s side, not over the top as usually depicted. Photo: NASA

The astronauts did not keep secret their discoveries. They conveyed them from space to the people on Earth who were following their mission and changed the way humans viewed their place in the universe.

As they came around the moon, the astronauts had a new vision of Earth, Presiding Bishop Michael Curry told a large crowd gathered at Washington National Cathedral on the evening of Dec. 11. “I wonder if, at some level, God whispered in their ears and said, ‘Behold. Behold the world of which you are a part. Look at it. Look at its symmetry, look at its beauty. Look at its wonder. Look at it. Behold your world,’” Curry said.

In addition to Curry, “The Spirit of Apollo” program at the cathedral featured Lovell, who also flew on Apollo 13, Gemini 7 and Gemini 12; Jim Bridenstine, NASA administrator; Ellen R. Stofan, director of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum; and the Very Rev. Randy Hollerith, dean of the cathedral. The five were invited to explore the spiritual meaning of exploration and the unity created by the mission’s Christmas Eve broadcast and the iconic “Earthrise” photo taken by one of the astronauts.

The program at the cathedral is one of a series of “Apollo 50” events leading up to a five-day celebration, July 16–20, 2019, at the National Air and Space Museum and on the National Mall to commemorate Apollo 11 and the first moon landing. The museum received $2 million from the Boeing Corp. to help pay for the cathedral event and all of the commemorations.

A view from the Apollo 8 spacecraft shows nearly the entire Western Hemisphere, from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, including nearby Newfoundland, to Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America. Central America is clearly outlined. Nearly all of South America is covered by clouds, except the high Andes mountain chain along the west coast. A small portion of West Africa shows as well. Photo: NASA

Hollerith suggested that Apollo 8 was “a holy journey not only for what it accomplished, but for what it revealed to us about our place in God’s grand creation.”

Curry mentioned that some believe “that moment changed human consciousness forever,” and he added that the view of Earth from space showed “we are a part of it, not the sum total of it.”

Lovell agreed, describing how he realized that his thumb could cover up the entire Earth as he saw it through the space capsule’s window. “In this cathedral, my world exists within these walls, but seeing the Earth at 240,000 miles, my world suddenly expanded to infinity,” he said.

“Just think: over 3 billion people, mountains, oceans, deserts, everything I ever knew was behind my thumb,” he said. “As I observed the Earth, I realized my home was a small planet. It is just a mere speck in our Milky Way galaxy and lost to oblivion in the universe.”

Lovell, who received sustained applause and a standing ovation as he approached the lectern to begin his remarks, said he began to question his own existence, asking, “How do I fit into what I see?”

Apollo 8 astronaut Jim Lovell: “To me this would be a mini Lewis & Clark expedition; exploring new territory on the Moon’s far side.” #SpiritofApollo pic.twitter.com/0rzGMnbK6z

— National Air and Space Museum (@airandspace) December 12, 2018

As a near-capacity crowd gathered in the cathedral, the same waxing crescent moon hung in the sky that people on Earth saw on that Christmas Eve, and the International Space Station passed overhead during the Dec. 11 event, Stofan noted.

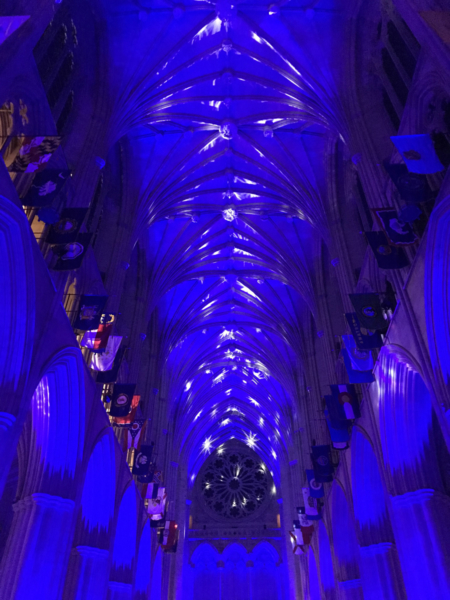

Images from space transform the exterior of Washington National Cathedral the night of Dec. 11, while inside, hundreds of people gathered to honor the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 8 mission. Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

On Christmas Eve 1968, the crew spoke to Earth’s inhabitants in what was then the most-watched TV broadcast. Anders began by describing the moon as “a rather foreboding horizon, a rather dark and unappetizing-looking place.”

“We are now approaching lunar sunrise,” he then said. “And, for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 have a message that we would like to send to you.”

Anders began to read the biblical story of creation. After he recited verses 1-4 of the first chapter of Genesis, using the King James Version, Lovell read verses 5-8 and Borman read verses 9-10.

“And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close, with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth,” Borman concluded the broadcast. It lasted just more than three minutes and was heard by an estimated 1 billion people around the world.

The mission commander, Borman, had been scheduled as a lector for the Christmas Day service at his parish, St. Christopher’s Episcopal Church in League City, Texas, until NASA moved up the launch date. “We kidded Frank about going to such lengths — all the way to the moon — to get out of … services,” the Rev. James Buckner told NBC News in 1999.

“Apollo 8 was full of surprises. We knew we were going to the moon. But hearing the story of creation beaming down to us on Christmas Eve, even the steely-eyed flight directors in Mission Control wept,” said Stofan. “Some of our bravest pilots and sailors, riding atop repurposed weapons of war, delivered a message of peace for all humankind. That was the spirit of Apollo.”

The nave of Washington National Cathedral was bathed in blue light and stars on the night of Dec. 11. Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

During the cathedral program, images of stars were projected on the vaulted ceiling of the nave and celestial images covered the building’s exterior. The Cathedral Choir performed “The Firmament,” which matched singing with a recording of the historic broadcast.

The iconic photo was a scramble to capture

“Earthrise” has been credited for inspiring the beginning of the environmental movement. It was included in Life magazine’s 100 Photographs That Changed the World issue. Anders once told NASA that the crew was just starting to go behind the moon when he looked out of his window and “saw all these stars, more stars than you could pick out constellations from.” Suddenly, “I don’t know who said it, maybe all of us said, ‘Oh my God. Look at that!’” as they saw the Earth rise.

The vision set off a scramble to record the scene as the astronauts searched for a color film camera for Anders. The transcript relays the fear of any photographer of missing the shot.

“We came all this way to explore the Moon,” Anders once said, “and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”

Curry mused on God’s reaction to Apollo 8. “I wonder if when they saw it, and then later we saw it, and when they read from Genesis, if God kind of gave a cosmic smile,” Curry said. “And I wonder if God said, ‘Now y’all see what I see.’ God says ‘y’all.’ It’s in the King James Version of the Bible.”

Curry urged those gathered to rededicate themselves to exploration, and to the preservation of Earth.

“My brothers, my sisters, my siblings, may this commemoration be a moment of re-consecration and dedication to mount on eagles’ wings and fly, to explore new worlds, to seek out vast knowledge, and then to mobilize the great knowledge of science and technology and the wisdom of humans to save this oasis, our island home,” he said.

Curry then began to sing “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,” the song that had been his refrain during his remarks. The Cathedral Choir slowly joined in, and at Curry’s urging, many in the gathering began to softly sing along.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry discusses Apollo 8’s impact on the world Dec. 11 while the Washington National Cathedral Choir listens. Photo: Danielle E. Thomas/Washington National Cathedral

The Apollo 8 mission had many dimensions

The mission and the Christmas Eve broadcast came at the end of a very trying year for a country that was “shaken by division and civil unrest,” in Stofan’s words.

The Tet Offensive in Vietnam at the end of January had shown the falsity of official claims that the war’s end was in sight. In April, Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated and riots broke out in more than 100 U.S. cities. Robert Kennedy was murdered in June after a presidential campaign appearance. Anti-war protests roiled cities and college campuses.

Officially, the mission was designed to test the Apollo command module systems and evaluate crew performance on a lunar orbiting mission. The crew photographed the lunar surface, both far side and near side, obtaining information on topography and landmarks, as well as other scientific information necessary for future Apollo landings.

The three Apollo 8 astronauts, left to right, James A. Lovell Jr., command module pilot; William A. Anders, lunar module pilot; and Frank Borman, commander, pose Nov. 13, 1968, beside the Apollo Mission Simulator at the Kennedy Space Center. Photo: NASA

It also aimed to give the United States a huge lead in the space race with the Soviet Union. The desire to beat the Soviets to the moon was precisely what made NASA decide, based on intelligence it received in mid-1968, that the USSR might be able to send astronauts to orbit the moon by the end of that year. In August, NASA turned Apollo 8 from an Earth-orbit test flight into a lunar mission. It was dangerous, and the three astronauts were, among other things, “Cold War warriors,” Bridenstine said in a press briefing before the event.

“Their Christmas Eve broadcast reached not just almost all of America, but tens of millions of people behind the Iron Curtain where Christmas was still illegal — and they reached them with a Christmas message,” Bridenstine said during the program. “That is an amazing tool of national power, of soft power. The idea that we can change the perception of people all around the world towards the United States with space exploration and discovery and science, and that’s what NASA did in the Christmas of 1968.”

The NASA administrator said the cathedral program was also about the future of America’s role in space exploration. He noted that President Donald Trump has told the country it is going back to the moon. “I want to be clear,” Bridenstine said. “We’re going forward to the moon. We’re doing it in a way that has never been done before. This time when we go, we’re going to stay.”

He described “sustainable, reusable architecture” that will utilize the resources present on the moon, including “hundreds of billions of tons of water ice at the poles of the moon.” Astronauts will repeatedly go to the moon with commercial and international partners, he predicted, because that water can sustain them and can be used to produce the rocket fuel needed to get home.

Rather than the “contest of ideas” that marked the first race to the moon, Bridenstine said this future effort’s technology will be open-sourced and available to any nation, as well as to companies or private individuals “that also want to plug into that architecture in a commercial way.” He also predicted that the moon effort would be replicated “in our journey to Mars.”

Artist Rodney Winfield of St. Louis, Missouri, created the design for the cathedral’s Space Window to symbolize the macrocosm and microcosm of space, and to show the minuteness of humanity in God’s universe. It is the only stained glass window in the cathedral that incorporates all three lancets into a single image. The night of the Apollo 8 celebration, the window was illuminated by three spotlights mounted on tall scaffolding outside the south side of the cathedral. Photo: Washington National Cathedral

National Cathedral has a cosmic connection

The cathedral has long honored space travel. Its so-called “Space Window” contains a 7.18-gram basalt lunar rock from the Sea of Tranquility, donated to the cathedral by the crew of Apollo 11 (Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins). The window was dedicated on the fifth anniversary of Armstrong and Aldrin’s lunar landing, July 21, 1974.

Hollerith, during his opening remarks, said the cathedral is “blessed to be stewards” of the 3.6-billion-year-old rock.

In January 1986, hundreds of mourners spontaneously came to the cathedral and laid wreaths of flowers beneath the window as a memorial to the scientists and technicians that it was designed to honor after the space shuttle Challenger exploded on liftoff. Then, 17 years later, the cathedral hosted the national memorial service for the seven-member crew of space shuttle Columbia, which disintegrated upon re-entry to Earth’s atmosphere on Feb. 1, 2003.

Armstrong, the first human to walk on the moon, was honored after his death in 2012 at a public service in the cathedral.

In a more prosaic vein, since 1986, a Darth Vader gargoyle, also known as a grotesque, has reigned over the dark north side of the cathedral from its perch high on the northwest tower.

Apollo 8 Astronaut James A. Lovell Jr. was the last speaker in the Dec. 11 event. He is seen here on one of the television screens used to help the gathering see the speakers. The cathedral’s Space Window, containing a piece of the moon, can be seen above. Photo: Danielle E. Thomas/Washington National Cathedral

Apollo 8 headed home with big news

Shortly past midnight on Christmas morning, after just more than 20 hours and 10 orbits of the moon, the crew made history again when it ignited an engine burn to leave lunar orbit and start for home. Again, that firing had to take place on the moon’s far side, out of radio contact with Mission Control. People there listened anxiously for confirmation that the burn had powered Apollo 8 out of lunar orbit and toward Earth.

“Roger, please be informed there is a Santa Claus,” Lovell radioed.

Read and see more about it

The on-demand broadcast can be viewed here.

The booklet for the Dec. 11 program is here.

The museum’s Apollo 50 page is here.

A NASA gallery of images from the Apollo 8 mission is here.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is the Episcopal News Service’s senior editor and reporter.

Social Menu