With in-person worship suspended, churches puzzle over how to count online attendancePosted Apr 22, 2020 |

|

The Rev. Ian Elliott Davies, rector of St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in West Hollywood, California, celebrates Easter on April 12 in a service livestreamed on Facebook. Photo: St. Thomas the Apostle, via Facebook

[Episcopal News Service] The pandemic is no match for the parochial report.

Episcopal congregations, despite suspending in-person worship services to help slow the spread of COVID-19, still are collecting a range of data that, when this year is over, will be included in the annual five-page report that Episcopal Church Canons require every congregation to file.

One of the report’s most referenced data points is “annual Sunday attendance,” often known by the shorthand ASA. But what counts as attendance while the pews are empty and hundreds are watching and listening from home? The Episcopal Church doesn’t yet have a precise answer, though one thing is clear during the coronavirus pandemic: Although in-person suspensions essentially have reduced physical Sunday attendance to zero, online worshipping communities are growing – and generating their own virtual attendance numbers, some easier to interpret than others.

In Baltimore, Maryland, the Cathedral of the Incarnation’s ASA has ranged from 250 to 300 in recent years, but with the Diocese of Maryland promoting its livestreams, Sunday services at Incarnation during Lent and on Easter have been watched more than 1,000 times each on YouTube. In Memphis, Tennessee, about 300 people had been attending services on an average Sunday at Calvary Episcopal Church. In-person worship is on hold, but virtual attendance remains strong, with video of the congregation’s April 19 service approaching 1,000 total views on Facebook.

And at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church, a small Anglo-Catholic congregation in progressive West Hollywood, California, the Rev. Ian Elliott Davies led a livestream Latin service on Facebook for the first time April 18. In-person attendance for his Latin services typically draw about 15, but the online service has been viewed more than 1,300 times – this “viral” spread seen as a positive.

“The message is traveling very quickly,” parishioner Geoff Clark-Tosca told Episcopal News Service. He serves as Davies’ cameraman, with his iPhone as the camera, during the congregation’s online services throughout the week, broadcast from a makeshift sanctuary in the rectory’s dining room.

Other churches across The Episcopal Church have found similar success reaching worshipping communities online. “It’s inspiring that worship is still going on via the internet, despite the bans on public gatherings,” the Rev. Michael Barlowe, the church’s executive officer and secretary of General Convention, said in a letter to dioceses last month. “The most important thing right now is the health of our people and our neighbors, so having the ability to worship over digital platforms has been a real blessing.”

Barlowe’s March 18 letter encouraged congregations to keep track of their online numbers, and he assured local leaders that specific guidance will be issued later this year on how to account for online engagement in light of the coronavirus’ disruption of in-person worship. Even so, the numbers are not an immediate concern, he emphasized, and anyone feeling “anxiety about how to document attendance” shouldn’t worry about the details.

That advice is seconded by the Rev. Chris Rankin-Williams. As chair of the House of Deputies’ Committee on the State of the Church, Rankin-Williams is leading efforts to revise the parochial report’s format. He thinks congregations and priests have long worried too much about ASA, at the expense of a fuller picture of church vitality.

“The only good casualty of this pandemic would be if it kills our obsession with ASA,” Rankin-Williams told ENS. “Of all the things you can spend time engaging on right now, worrying about your ASA is not a productive one.”

Instead, many churches are proving their vitality during the coronavirus pandemic as they respond to disruptions to parish life by reaching their communities in new ways, Rankin-Williams said. As they re-envision what it means to be worshipping communities in the digital age, these lessons won’t be unlearned when the public health crisis is over.

“It’s not clear to me the church is ever going to be the same after this,” he said.

Online numbers highlight ‘church community all the time’

Leaning into this new normal, St. Thomas the Apostle initiated a new shorthand. Instead of ASA, the attendance number is marked as “LS,” for livestream viewership. It can be counted at least two ways: by how many people watch a service while it is being streamed on Facebook, and by how many have viewed the video of the service at the end of the day.

Services in Latin aren’t common at Episcopal churches, but this one found its congregation. At its peak live viewership, the April 18 service reached 51 people, Clark-Tosca said. Live numbers have been about the same for weekday services and a bit higher on Sunday. Those results are modest successes for a church that in recent years has averaged about 150 for in-person Sunday attendance.

A rise in online viewership in early March coincided with public health concerns, which prompted Los Angeles Bishop John Harvey Taylor’s March 5 decision to suspend distribution of wine at Communion in the diocese as a precaution against the coronavirus. Taylor followed up with an order March 17 suspending worship services, and since then, some digital metrics have far exceeded St Thomas the Apostle’s in-person numbers.

Most of the diocese’s 134 congregations now offer some sort of Sunday worship online and are seeing positive results, Taylor said in an interview with ENS. Online services may not fully replace the experience of in-person worship, he said, but it has proven to be an invaluable resource in these difficult times.

“Just seeing one’s pastor on screen saying the prayers and offering a word of encouragement is enough church for a lot of people right now,” Taylor said. He also thinks the expansion of online faith experiences throughout the week, from weekday prayer services to Bible studies by video conference, offers a welcome reminder: Being the church doesn’t start and end with Sunday morning.

“What it’s showing us is that we’re a church community all the time,” Taylor said. As Christians, “this thing we do is supposed to be with us every hour of every day.”

Taylor acknowledged that comparing online viewership to average Sunday attendance may be a matter of apples and oranges. It’s hard to tell whether Facebook viewers are fleeting or truly engaged with the services, though Taylor added that in-person church attendance doesn’t guarantee a parishioner is paying attention through the sermons.

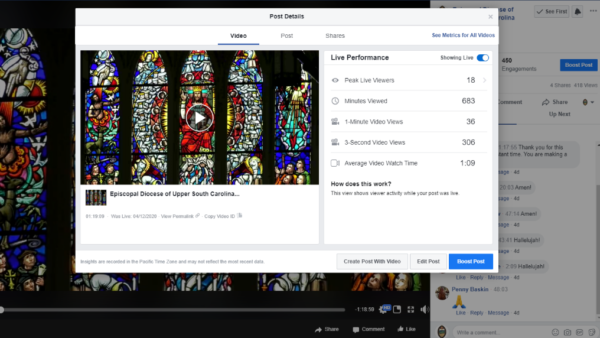

In the Diocese of Upper South Carolina, the Rev. Alan Bentrup, canon for evangelism and mission, posted guidance to the diocese’s website after fielding various inquiries from priests and lay leaders about how best to track digital engagement. Even some small parishes are livestreaming services, but the metrics used by Facebook, YouTube and other platforms can be confusing, he said.

Facebook, for example, tracks both three-second views and one-minute views for livestreams, and Bentrup compared the three-second view to someone simply driving by a church on a Sunday morning. That person would never be considered part of the ASA. “If someone watches for a minute, there’s at least some level of engagement,” he said, and each view could equate even larger participation, since more than one person may be viewing on each device.

For now, he has this advice for churches: “Pick a metric and just continue to track that one.”

The Diocese of Upper South Carolina shared this screen grab of a Facebook video’s metrics in offering guidance for congregations on how to track virtual worship participation.

Taylor has advised congregations in the Diocese of Los Angeles to capture data on their online communities but to not yet consider it as part of their official attendance figures until churchwide officials issue further guidance. Likewise, Bishop Sean Rowe, bishop diocesan for Northwest Pennsylvania who also serves as bishop provisional for Western New York, asked his 93 congregations to track whatever numbers they can. “Then we will work to interpret them later according to a common set of guidelines,” Rowe told ENS.

Rowe also suggested local leaders track the number of phone calls made to check on parishioners, because in his largely rural dioceses, not everyone has the reliable internet or cell service needed to participate in livestream worship.

The partnership between Rowe’s two dioceses is now a year old, under a five-year plan to share a bishop and coordinate resources together that has been closely watched by church leaders across The Episcopal Church. When Rowe agreed to lead both dioceses, he saw opportunities to rethink church vitality with a focus on mission, and that approach may help the dioceses’ congregations during the current crisis as they look beyond the traditional metric of average Sunday attendance.

“I hope this experience helps us dig deep into what we understand as the mission and role of our congregations, and what vitality means,” he said. “I think this is going to push us to say what that is and figure out a way to measure it.”

Beyond ASA, a renewed focus on church vitality

Barlowe’s letter to dioceses said guidance on measuring attendance will be issued in time for the 2020 parochial reports to be filed in early 2021. By then, “we will have more experience with this, and we will have had time to consider, consult and offer more guidance,” Barlowe said. “We have time, as we pray for an end to this pandemic.”

Changes to the parochial report already were underway. In 2018, the 79th General Convention passed a resolution calling on Executive Council “to design a simplified parochial report relevant to the diversity of The Episcopal Church’s participation in God’s mission in the world.” The report’s development was assigned to the House of Deputies’ Committee on the State of the Church.

The Canons require congregations to report “baptisms, confirmations, marriages, and burials during the year,” as well as the number of baptized members and communicants. Average Sunday attendance, though not a number explicitly required by the Canons, has long been tabulated by The Episcopal Church and referenced by its congregations, said Rankin-Williams, the committee chair.

“ASA has been cast as this way we evaluate each other,” Rankin-Williams said. “That’s a mistake. … It’s not clear to me that it’s actually a measure of vitality.” Possible changes to the parochial report include additional demographic data, a fuller account of parishioners’ outreach participation, and a narrative section where church leaders can describe how they see their role in the Jesus Movement, he said.

Ultimately, the decision on how to record attendance during in-person worship suspensions will be made by Executive Council, which meets next in June, likely as an online conference. It isn’t clear yet whether parochial reports and attendance tracking will be on the agenda for that meeting. Rankin-Williams thinks the solution likely will entail reporting a traditional ASA alongside some virtual metric.

Bentrup, in Upper South Carolina, also raised the possibility that online numbers during this pandemic may be recorded but not used in formulas, such as clergy compensation, that traditionally have relied on ASA – in the same way that some schools are removing this semester from their calculations of students’ grade-point averages.

Rankin-Williams is rector of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Ross, California, north of San Francisco. It has an ASA of just above 200, but twice that number of participants have joined its livestream services, Rankin-Williams said. He isn’t sure churches’ online surge will continue at the same levels when in-person worship resumes.

“The next five years of the church are being compressed into the next five months,” he said. The pandemic may accelerate the closure of some churches, while others are adopting technology to encourage discipleship, evangelism and growth. “Right now, you see people connecting to church in some really fascinating ways.”

The Rev. Ian Elliott Davies has led worship services from the dining room of the rectory at St. Thomas the Apostle Episcopal Church in West Hollywood, where, as with all video productions, there is some amount of down time, often with canine companionship. Photo: Geoff Clark-Tosca

At St. Thomas the Apostle in the Diocese of Los Angeles, Clark-Tosca and a small group of parishioners had been looking for ways of improving the congregation’s digital presence for several months, since attending a session on digital evangelism at a diocesan ministry fair. When the pandemic hit, they realized they needed to ramp up those efforts quickly.

Viewers seemed to prefer services broadcast from the more intimate setting of the rectory, including weekday prayer services, and Clark-Tosca thinks improving the audio and video quality of the livestreams has made a big difference. If this is the new normal for St. Thomas the Apostle’s presence online, the congregation isn’t going back.

“This is now part of our congregation,” Clark-Tosca said, and they won’t “let it slide” when they resume in-person worship. “We see people need this.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu