Despite setbacks, The Episcopal Church and Alaska Natives step up fight against drilling in Arctic refugePosted Aug 29, 2019 |

|

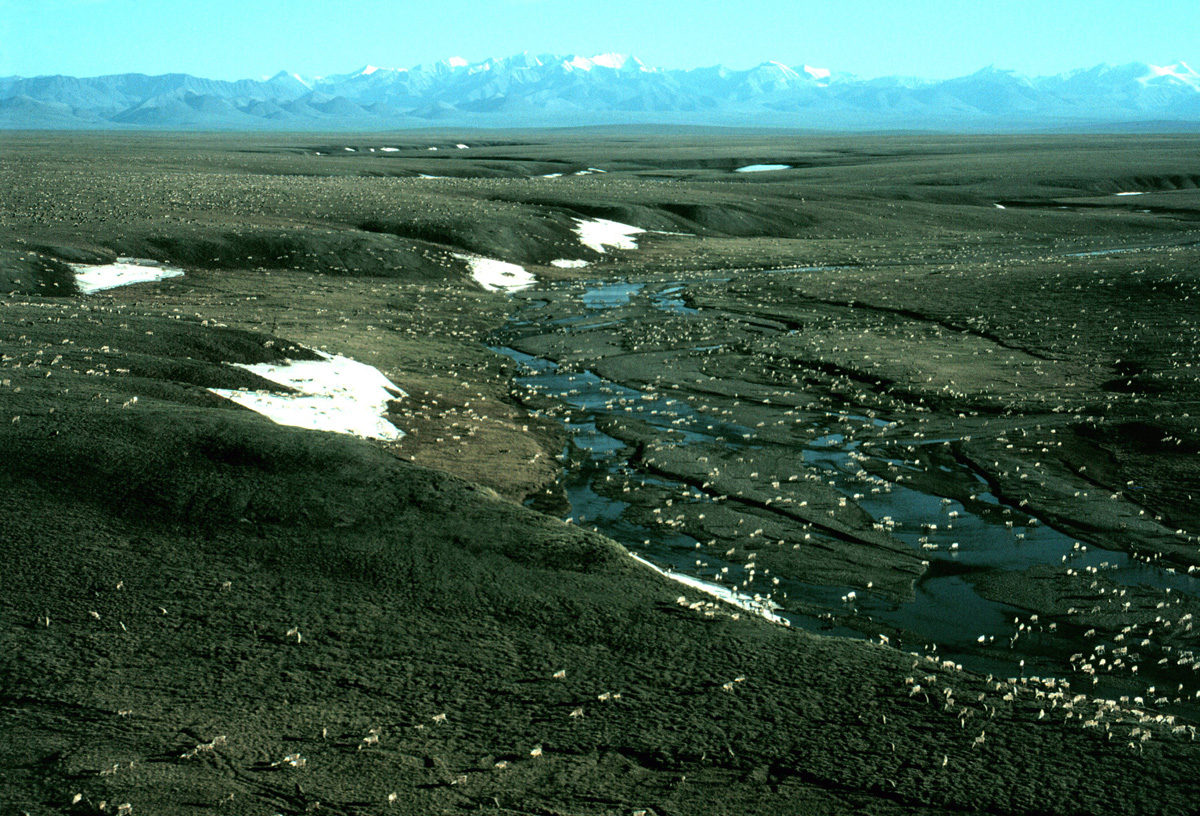

The Porcupine caribou herd in the 1002 area of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Coastal Plain, with the Brooks Range mountains in the distance to the south. Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

[Episcopal News Service] For Bernadette Demientieff, rediscovering her identity as a Gwich’in – one of the indigenous peoples of the Arctic – meant reconnecting with the land. Specifically, a mountain called Duchanlee near Arctic Village, Alaska, in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, a place that holds deep significance to her people.

“When I went there, I don’t know what came over me,” she told Episcopal News Service. “I just started crying.”

“I lost my identity after high school,” she said. “I kind of went down the wrong path.”

But on that mountain, something changed.

“And right there, I asked Creator for forgiveness, for being disconnected so long, but that I’m here now to share my responsibility as a Gwich’in,” she said.

Bernadette Demientieff speaks on July 10, 2018, at the 79th General Convention in Austin, Texas. Photo: Sharon Tillman/Episcopal News Service

For Demientieff, that responsibility includes protecting the lands and animals that have sustained her people for thousands of years. Now 43, she is a central figure in the coalition of Gwich’in, Episcopalians and conservationists that has fought to prevent industrial development from disrupting the ecology of the refuge’s most sensitive area. She is the executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, which calls itself “the unified voice of the Gwich’in Nation speaking out to protect the Coastal Plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge” from the oil industry. She is also a member of The Episcopal Church’s Task Force on Care of Creation and Environmental Racism and has spoken to the House of Bishops and the General Convention about the importance of protecting the refuge.

Demientieff plans to be in Washington in September to advocate for an expected House of Representatives floor vote to restore protections for the Coastal Plain, which was opened to drilling by Congress in 2017 despite decades of vocal opposition from the Gwich’in, The Episcopal Church and many other groups from around Alaska and the U.S.

Now, with the prospect of drilling in the refuge closer to reality than ever, Episcopal and Gwich’in leaders say they’re not giving up — especially in the face of the climate crisis, which is already wreaking environmental havoc in Alaska.

“It’s not over,” Demientieff told ENS. “It just started.”

The Sacred Place Where Life Begins

The Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which occupies the northeast corner of Alaska, is so vast it’s difficult to comprehend. At 19.6 million acres – about the size of South Carolina – it is the largest wildlife refuge in the United States, stretching from the forests of Alaska’s Interior across the Brooks Range to the Coastal Plain tundra, all the way to the Arctic Ocean.

Image: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

The refuge has been inhabited by Native peoples for thousands of years. The Iñupiaq live along Alaska’s northern coast, while the Gwich’in have traditionally inhabited an area that includes the interior of the refuge and stretches east into Canada. Besides the Iñupiaq village of Kaktovik on the Arctic coast and the Gwich’in settlement of Arctic Village on the refuge’s southern boundary, there are virtually no traces of human activity in the massive refuge.

Mountain ranges and waterways in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

In fact, the area the Gwich’in have been trying to protect from drilling – the Coastal Plain – is not part of their ancestral homeland. Although the Gwich’in traditionally followed the Porcupine caribou herds during their seasonal migrations around the region, the “one place that the caribou go that we do not is the Coastal Plain,” Demientieff testified during a congressional hearing in March.

But the reason they have avoided the area for so long is the same reason they are trying to protect it now: the Coastal Plain is where the caribou go to give birth and nurse their calves every summer.

Caribou in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

“This area is sacred to our people,” Demientieff testified, “so sacred that during the years of food shortage we still honored the calving grounds and never stepped foot on the Coastal Plain.”

The Porcupine caribou herd – named after the Porcupine River – is crucial to the culture of the Gwich’in, and to their very existence. Life in the Gwich’in villages revolves around the subsistence economy – hunting caribou, fishing and gathering. All but one of the Gwich’in villages are isolated from the state road system, so whatever food and supplies are flown in from elsewhere tend to be about three times as expensive as they are in a typical Lower 48 supermarket: A gallon of milk at a village store in a place like Fort Yukon or Arctic Village costs at least $10, as does a gallon of gas, and when something like a watermelon makes a rare appearance, it can go for around $40. If the caribou’s breeding or migration patterns were disrupted, there would be few other options for affordable food.

The Porcupine caribou have the longest land migration of any animal in the world, traveling more than 1,500 miles per year from their wintering grounds in the Interior to the Coastal Plain, which the Gwich’in call “Iizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit” – “the Sacred Place Where Life Begins.”

Open for business

That same area, however, has attracted the interest of the fossil fuel industry for decades because it could contain massive oil deposits. The Prudhoe Bay oil field, by far the largest in North America, sits on the coast to the west of the refuge. Its discovery in the 1960s radically altered the economic, demographic and cultural makeup of Alaska. It has also forever changed the landscape; what was once an unspoiled frontier along the Arctic Ocean is now a hub of heavy industry.

Today, the oil and gas industry provides over one-third of Alaska’s jobs and about 90 percent of the state’s revenue. Because of Alaska’s reliance on the oil and gas industry, the state economy since the 1970s has been a series of dramatic booms and busts. The state once had so much oil revenue flowing in that it literally didn’t know what to do with it, so it set up a fund that continues to pay each citizen a dividend of around $1,000 every year. But oil production at Prudhoe Bay has slowed, and since prices plummeted in 2015, the state has been steadily shedding revenue, residents and jobs. Alaska now has the highest unemployment rate in the U.S., at 6.3 percent in July. On Aug. 27, BP – which has been in Alaska for 60 years and operates the Prudhoe Bay oil field – shocked the state by announcing it will sell all of its Alaska assets, the latest sign of turmoil in the industry. With legislators refusing to implement a state income or sales tax, the state has blown through billions of dollars in savings and has been embroiled in a budget crisis for several years. This summer, a drawn-out political battle has erupted over Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s severe budget cuts, including a proposed 40 percent cut to the University of Alaska system.

The prospect of a large oil field beneath the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s Coastal Plain – bringing with it the jobs and revenue that Alaska desperately needs – has made opening it up to development a top priority for the state’s congressional delegation for decades. When the refuge was created, the “1002 area” – 1.5 million acres of the refuge’s Coastal Plain – was set aside for possible development, which required congressional authorization.

Nearly 50 times, Republicans tried and failed to unlock the 1002 area. But in December 2017, a provision to open the area to drilling was tucked into the tax bill signed by President Donald Trump. It appeared that the coalition of the Gwich’in, The Episcopal Church and environmentalists had lost the battle.

‘This is our family’

The Episcopal Church, through its Washington-based Office of Government Relations and the Diocese of Alaska, has been a leader in that fight for decades because of its deep historical connection to the Gwich’in people and its broader commitments to environmental protection and indigenous rights.

The link between the Gwich’in and The Episcopal Church dates back to the 19th century, when Episcopal and Anglican missionaries brought Christianity to the Gwich’in. One of those missionaries, Robert McDonald, created the written form of the Gwich’in language and translated the Bible and the Book of Common Prayer.

“In Alaska, where The Episcopal Church began to take root was in Gwich’in country,” said Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime. “And so, as a diocese, we have recognized that this is our family. These are our people. And we have wanted to do what we can to stand and walk with them and support them.”

The coalition of The Episcopal Church, the Gwich’in Steering Committee and the Alaska Wilderness League has been a constant presence at congressional hearings for years, most recently on March 26 at a heated hearing on a bill that would have repealed the refuge-opening provision in the 2017 tax law. Lattime and Demientieff both testified in support.

Gwich’in clergy and Alaska Bishop Mark Lattime (top right) gather for a photo at St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church in Fairbanks in June 2014, after a Eucharist celebrated in a dialect of the Gwich’in language. Photo courtesy of Scott Fisher

Back in Alaska, Lattime has spoken and prayed at rallies and public forums and participated in a TV ad campaign. He said he tries to be as helpful as he can to the Gwich’in’s cause without speaking for them.

“We’ve been very careful and intentional to listen to their voices and to follow their lead and do what we can to respond as they have asked us to do,” he said.

Although the opening of the refuge was a major blow, the situation is still evolving. With Democrats now controlling the House of Representatives, hearings like the one in March offer new opportunities for advocacy. The Interior Department says lease sales will begin by the end of this year, but the combination of regulatory hurdles and volatility in the price of oil means it could be many years before any drilling happens. It’s also possible that the 1002 area contains much less oil than was originally speculated, making it economically unviable to drill there. For now, the Office of Government Relations continues to advocate for legislation that would at least introduce new restrictions on drilling in the refuge, such as a provision that would require oil lease sales in the Coastal Plain to be priced high enough to produce the revenues anticipated by the 2017 tax bill, which are much higher than what the current market value would be, according to domestic and environmental policy adviser Jack Cobb.

The Episcopal Church’s efforts on environmental protection and climate justice go beyond its Capitol Hill advocacy. At the 2015 General Convention, a resolution directed the church’s Executive Council Investment Committee to divest from fossil fuels “in a fiscally responsible manner.” Treasurer and Chief Financial Officer Kurt Barnes estimates the church’s portfolio now has about 2 percent exposure to the fossil fuel industry. However, that resolution did not apply to the much larger Church Pension Fund. In its report to last year’s General Convention, the Church Pension Group said it is not opposed to divestment but can only do it if it doesn’t interfere with its fiduciary responsibilities. CPG does not disclose the amounts of specific securities in its portfolio, but says it is focused on socially responsible investing and shareholder advocacy, said Curt Ritter, CPG senior vice president and head of corporate communications.

Demientieff’s approach going forward is more direct.

“I will stand up even until the first oil rig goes in,” Demientieff said.

An uncertain future

Alaska Natives are not universally opposed to drilling in the refuge, though. Among the Iñupiaq people who live on the Coastal Plain, there is strong support for increased oil and gas development. Unlike the Gwich’in, the Iñupiaq benefit from the industry in the form of local tax revenues, corporate dividends, better village infrastructure and local jobs. Those who support drilling in the Coastal Plain say development there would be safer and leave a much smaller footprint than it has in Prudhoe Bay. At the same hearing where Lattime and Demientieff testified in support of protecting the Coastal Plain, several Iñupiaq witnesses testified against it.

Caribou walk across a gravel pad at Kuparuk, 45 miles from Prudhoe Bay, with oil field facilities in the background. Photo: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

“I’m not trying to take jobs from anybody,” Demientieff told ENS. “I’m not trying to tell anybody what to do. But honestly, that is considered federal land regardless of who lives right beside it. And just because I don’t live close to it does not mean that I will not be impacted by what happens there.”

And by perpetuating the burning of fossil fuels, drilling in the refuge would contribute to the effects of the climate crisis that are being felt more severely in Alaska than almost anywhere else. The state has warmed twice as fast as the rest of the U.S. in the past 60 years, with average winter temperatures rising by six degrees Fahrenheit during that time, according to the Environmental Defense Fund. Amid record-high temperatures, the sea ice that once protected coastal villages from erosion has dramatically retreated, causing problems for Native subsistence hunters who need sea ice to hunt seals, whales and walruses. Permafrost beneath villages is thawing rapidly, causing land to sink and often leading to erosion. Entire villages are moving to higher ground. Warm water is causing salmon die-offs, threatening a major source of the state’s food supply and economic base. Wildfires are becoming an increasingly common threat.

A section of coastal bluff, with visible permafrost, collapses at Drew Point on Alaska’s North Slope. Photo: Benjamin Jones/U.S. Geological Survey

“All the elders that I interview and talk to, they’ve never seen anything like this before,” Demientieff said.

The Rev. Trimble Gilbert speaks at a meal in Nenana, Alaska, during the House of Bishops’ visit in 2017. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

One of those elders, the Rev. Trimble Gilbert, has lived in Arctic Village for nearly all his 84 years. An Episcopal priest and traditional chief, Gilbert has a unique perspective on climate change, combining his own experience with stories passed down from his ancestors. He can point to specific examples: polar bears moving into villages in search of food, fish depleted where they used to be plentiful.

“I could see a lot of change [in the] last 30 years,” he told ENS. “It’s gonna be a pretty sad place in the next 50 years if they’re gonna [drill] … I could see it now. So I hope they can stop and protect the land.”

In the meantime, he finds solace in living off the land, as his ancestors did, and he tries to keep those traditions alive.

“We still try to live our traditional way of life, sharing and taking care of each other almost every day,” he said.

Demientieff says her spirituality and maintaining a traditional way of life also sustains her in the fight.

“I take the time to pray every morning,” she told ENS, adding that she needs it just as much as food or sleep. “When I don’t stay strong in prayer … it’s draining.”

“God gave us this land to take care of,” Demientieff said. We should be taking care of our blessings. We should always take care of what God put in our hands to take care of for him, not to drill it and destroy it.”

– Egan Millard is an assistant editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at emillard@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu