All Our Children network’s end offers tough lessons for Episcopal work on education equity, povertyPosted Aug 2, 2019 |

|

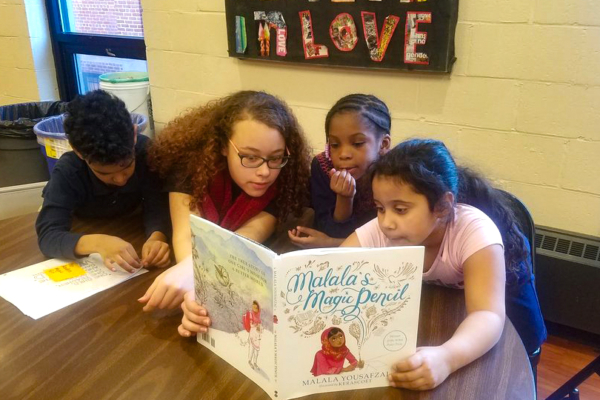

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Boston worked with suburban churches to create a library at Blackstone Elementary School in 2011. St. Stephen’s has for years developed relationships with the school’s students, parents and teachers through its after-school program. Photo: St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church

[Episcopal News Service] Sixty-five years after the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed segregation in Brown v. Board of Education, the American public education system remains overwhelmingly separate and unequal. In February 2019, the advocacy organization EdBuild put a number on the problem: $23 billion.

That is the national funding gap between mostly white and mostly nonwhite school districts, despite comparable numbers of students, EdBuild found. Inequitable funding policies that prioritize where a child lives over communities’ financial resources have “led to an endlessly unfair system that is stacked against our most vulnerable children,” the report concludes.

For evidence, look no further than the library at Blackstone Elementary School in Boston. A decade ago, the school didn’t have one.

What Blackstone had back then was a growing partnership with the neighboring St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, a largely black and Latino congregation in Boston’s South End. For years, church volunteers had developed relationships with teachers, students and parents through St. Stephen’s after-school program. The church also welcomed volunteers from white suburban churches, who were appalled to learn Blackstone had no library. In 2011, the suburban church volunteers helped open a library at the school, and they continue today to staff it.

“When they understood more about education equity, they were ready [to act], because they knew the kids,” the Rev. Liz Steinhauser, the church’s youth programs director, told Episcopal News Service.

Successful church-school partnerships start with listening and grow through personal relationships, Steinhauser and other members of The Episcopal Church’s All Our Children network told ENS. But their local ministries weren’t enough to sustain a national network of dioceses and congregations championing education equity. After seven years, All Our Children is disbanding. In a July 10 email to supporters, network director Lallie Lloyd cited long-term financial uncertainty, limited churchwide support and challenges related to “our previously unexamined internalized white supremacy.”

[perfectpullquote align=”right” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Established education ministries interested in applying for one of All Our Children’s grants have until Aug. 8 to submit applications. Info is at allourchildren.org/grants.[/perfectpullquote]

All Our Children formed in 2012 as the churchwide successor to a Diocese of New York ministry of the same name. With significant startup funding from New York’s Trinity Church Wall Street, it held trainings, webinars and conferences for people, like Steinhauser and her team, who are driven by their faith to the work of eliminating systemic inequality in American public education.

The network’s greatest accomplishment, according to church leaders interviewed by ENS, was to bring together Episcopalians engaged in similar ministries to learn from and support each other. Despite those successes, however, All Our Children couldn’t overcome what even its top supporters now see were ill-fated blind spots, particularly those related to white privilege and the evolving social justice priorities of The Episcopal Church.

The network has $80,000 remaining in unrestricted donations that it is in the process of distributing as grants to diocesan and church ministries. Applications will be accepted through Aug. 8, with the grants to be awarded in September.

“We believe, and have from the beginning, the unequal educational opportunities have deep structural roots,” Lloyd said in an interview with ENS. The network’s grants will target established ministries that have demonstrated an understanding of that dynamic. “We have never wanted to be only about charitable service to the children in our communities.”

All Our Children Director Lallie Lloyd speaks at the network’s January 2018 symposium at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Columbia, S.C. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

Examples of active church-school partnerships are plentiful, but the national network’s emphasis on systemic change generated only mixed results at the local level.

“We thought that if congregations partnered with local schools, their relationship would evolve from charitable direct service into public advocacy,” Lloyd said. “I think we would have to conclude that that doesn’t necessarily happen.”

Zakiya Jackson agrees. She is vice president of training and resources for The Expectations Project, an advocacy organization that works with faith-based groups to promote education equity, and for the past year, she has served on the All Our Children board. She helped Lloyd organize the Episcopal network’s January 2018 symposium in Columbia, South Carolina.

Zakiya Jackson of The Expectations Project served for a year on All Our Children’s board after helping to plan its January 2018 symposium. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

“Something that starts off as service can pivot to advocacy. … But it can also stay service,” Jackson told ENS. “Without that intentionality from the beginning, I think it unintentionally sets people up to think that taking care of children is equity work, and that’s not the same thing.”

A church volunteer’s pivot to advocacy typically hinges on a “conversion experience,” Steinhauser said, such as when her volunteers learned Blackstone didn’t have a library. Conversions often happen locally, though inequity in education is a nationwide problem.

“Low-income students and students of color are often relegated to low-quality school facilities that lack equitable access to teachers, instructional materials, technology and technology support, critical facilities, and physical maintenance,” the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights said in a 2018 report on public education funding.

Nearly one in four students in the United States attends what the U.S. Department of Education deems as high-poverty schools, filled disproportionately with nonwhite students. The department’s latest Condition of Education report shows about 45 percent of black and Hispanic students went to high-poverty schools in 2016, as opposed to only 8 percent of white students.

“White supremacy wasn’t an accident, and inequity’s not an accident,” Jackson said. “We didn’t get here just because a few folks started neglecting kids. Everything was intentional.” Creating an equitable education system, then, “takes more study and more skill and more fervor than I think we often realize.”

Decade of growth in network of churches focused on education

The initial fervor behind All Our Children goes back to a book lent to Bishop Catherine Roskam in 2006: Jonathan Kozol’s “The Shame of the Nation.”

The book was an indictment of the resegregation of American public schools, and Roskam, who was bishop suffragan of the Diocese of New York at the time, found its contemporary portrait “absolutely shocking.” She began noticing Kozol’s themes playing out in the neighborhoods that were home to the diocese’s churches.

Many of the congregations had no relationships with their local schools. She started All Our Children to encourage connections between churches and schools, often bridging racial divides in the process.

“I’m a person that looks a lot at what people can do immediately,” Roskam told ENS. Parishioners may be easily discouraged, wondering what one person can do to make a difference. “I think the answer to that is, one person can do a lot. At least, one person can do something.”

Congregations of all sizes got involved, Roskam said. Parishioners served as chaperones on a Mount Vernon school’s field trips. They created a community garden at a Monroe school. The started an arts program at a school in Bronxville.

“We were transformed by what we saw, and when that happens, you don’t go away and forget about that,” Roskam said.

By the time Roskam retired in January 2012, leaders of Episcopal education ministries around the country had begun networking on their own. In October 2012, their conversations spawned an inaugural conference, convened by Trinity Wall Street and hosted by St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia, that launched the national All Our Children network. The Rev. Ben Campbell, a pastoral associate at St. Paul’s, detailed that church’s longtime partnership with Woodville Elementary School, which had grown into the citywide Micah Initiative, with 125 worshipping communities of all faiths sending volunteers into about 25 elementary schools. Other Episcopal leaders shared stories of their experiences, from Cleveland to Dallas. Such examples “gave me a new sense for what’s possible,” Steinhauser said.

The Rev. Liz Steinhauser is director of youth programs at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Boston. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

“I think my work [and] other people’s work is better, stronger and more creative when we’re connected to other folks,” she said, “being part of something larger than ourselves.”

Lloyd was there representing Trinity Church Boston, and she soon was tapped to lead the national network as director. Trinity Church Boston agreed to serve as fiscal agent for All Our Children, which never incorporated as a separate nonprofit.

After working as an education programming grants officer at Pew Charitable Trust, Lloyd had been providing consulting services for nonprofits in the Boston area and wanted to get more involved in faith-based efforts on the issue of education equity.

“I felt a very strong longing to be able to use the moral passion that I find in my faith to talk about these inequities as a moral and ethical issue,” she told ENS.

Trinity Wall Street remained the network’s largest financial backer, awarding about $850,000 in grants to All Our Children through 2019 that helped to cover staffing costs, travel to conferences, and the regional and national gatherings of Episcopal leaders that kept up the network’s momentum.

“What I think Lallie and her colleagues were endeavoring to do was to make it a more national and less regional effort,” Massachusetts Bishop Alan Gates told ENS. He was a strong supporter of All Our Children, but the more effective networking seemed to happen locally, he said. “When we get together nationally, people’s contexts are so different.”

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral volunteer Beth Yon shows a student some of the finer points of sewing a hem during an activity in 2018 at W.A. Perry Middle School in Columbia, South Carolina. The Diocese of Upper South Carolina has been active in education ministries and advocacy through the ecumenical Bishops’ Public Education Initiative. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

Upper South Carolina Bishop Andrew Waldo echoed those sentiments. His diocese hosted All Our Children’s biggest gathering, a three-day symposium in January 2018. But the symposium, nominally backed by a General Convention resolution, barely drew more than 100 participants. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry was scheduled to preach but canceled due to illness.

“They did a wonderful job of trying to connect across the country,” Waldo said in an interview, expressing gratitude for Lloyd’s hard work. “To be a resource to congregations over such a geography might have been the most difficult part.”

Lloyd alluded to that reality in her July 10 email to supporters. “Most people called to this work are called to serve their local communities and have limited capacity for the additional labor of building a national network,” she wrote.

The network also struggled to raise enough money to make up for discontinued grants from Trinity Wall Street, which chose to phase out its financial support this year, Lloyd told ENS. And despite General Convention’s support for equity work, Episcopal leaders churchwide did not always share the enthusiasm of Gates, Waldo and a handful of other bishops, Lloyd said.

Hope and caution for future of education equity work

Lloyd hinted at a more fundamental challenge with her reference to “white supremacy” in announcing the end of All Our Children. Lloyd told ENS she was acknowledging, as a white woman and a lay leader in a predominantly white Christian denomination, that she had not fully appreciated how All Our Children’s early development was hindered by power structures that privilege whiteness – through a lens that sees equity work as giving something of value to people in need.

“That feels like toxic charity. It feels patronizing,” she said. “The danger is the way we talk and behave – in that way, we keep ourselves separate from the community around us.”

All Our Children, from the start, lacked grounding in a coalition of diverse community partners, something that changed somewhat when Lloyd began collaborating with Jackson and The Expectation Project.

By then, it may have been too late.

Church-school partnerships are “not the same thing as creating an equitable school environment or creating an equitable school district,” Jackson said. “That requires a different sort of understanding of justice, a different understanding of whiteness.”

Getting congregations and parishioners to that understanding often requires a leader who is an “agitator,” she added, a role not many people are comfortable filling.

Steinhauser, for her part, has years of experience as a community organizer and is comfortable preaching on what might seem like thorny topics.

But agitator? She suggested looking no further than the Gospel.

The Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas picked up the theme in an interview with ENS about how education equity and race intersect with social justice issues, which she has elevated as dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

“Social justice work isn’t the extra. It’s the Gospel,” said Douglas, who also serves as Washington National Cathedral’s canon theologian. “That’s indeed why the presiding bishop has called us back into the Jesus Movement.” Social justice work shouldn’t be optional for Christians, she said. “This is what we call white privilege, the privilege of not doing it.”

But how to do it right? Even the word “advocacy” carries the wrong connotations if it doesn’t first empower communities who have been disempowered by an unjust system, she said.

“Before the church reaches out, the church needs to educate itself,” she said. “We don’t want to devolve into this old missionary model that The Episcopal Church was very good at, as if we were doing for a people what they can’t do for themselves.”

Lloyd has attended a range of conferences to engage a broader spectrum of Christians and education advocates, from the Union of Black Episcopalians to something known as the Justice Conference. It was at the latter event, in 2016, that she met Jackson. The next year, they teamed up to lead a workshop at another conference, and Jackson agreed to help Lloyd plan the 2018 symposium in South Carolina.

Campbell, the Richmond priest, said he thought highly of the “incredibly valiant work that Lallie and her staff did.” He also thought it helped to bring The Expectations Project on board, but he questioned whether a broad coalition of partners was something that could be effectively added midstream.

“What would have happened if she had been able to be a part of a coalition like that from the beginning?” Campbell wondered. “I don’t know.”

With the official network closing down, All Our Children members hardly see this as The Episcopal Church’s final word on education equity. The Rev. Rainey Dankel is among the hopeful.

“I would not be surprised if individual relationships that came about as a result of that work do continue, because I think that we’re always trying to figure out better ways of doing what we’re doing,” said Dankel, who retired in March after seven years as associate rector at Trinity Church Boston.

Dankel said she grew to appreciate that, in successful school partnerships and advocacy, “a lot of it has to do with, frankly, confronting white privilege and racism,” especially in Boston, where students of color are a majority in the public schools. It’s more than “just showing up with good intentions trying to fix some kids.”

“We’re actually engaged in confronting and trying to transform both ourselves and our communities of which we are a part,” Dankel said, “which is a fundamental task of churches, that we are in the business of being transformed of God’s love and confronting our own complicity with the things that block people from experiencing that love.”

She told a story of Trinity Church Boston’s relationship with McCormack Middle School. The church helped create a library at McCormack, similar to St. Stephen’s partnership with Blackstone. When a teacher at McCormack brought a class into the library for the first time, Dankel recalled one boy looking around in awe.

“Wow,” the boy said. “This is so nice. What did we do to deserve this?”

“Which is just so heartbreaking,” Dankel told ENS, “that he didn’t know that he deserves that.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu