As Episcopal Church pushes to end mass incarceration, New York church takes up bail reformPosted Feb 4, 2019 |

|

The Rikers Island prison complex (foreground) is seen from an airplane in the Queens borough of New York. Photo: Reuters

[Episcopal News Service] The Episcopal Church’s General Convention, in addition to placing racial reconciliation among the church’s top priorities, has voted since 2015 to emphasize criminal justice reform as an essential step toward ending the American system of mass incarceration that disproportionately punishes people of color.

An example of that system – and, for reformers, an opportunity – can be found on an island in the middle of New York’s East River.

Rikers Island is the city’s primary incarceration site, home to eight inmate facilities that hold most of the more than 8,000 people in New York City who in an average day are held behind bars while they wait for a court hearing or trial, or as they serve their jail sentences. More than half of the city’s inmates and detainees are black, and a third are Hispanic.

Last fall, members of Trinity Church Wall Street, an affluent parish in Lower Manhattan, joined a “mass bail out” of certain detainees being held at city jails. The congregation is on the front lines of a movement to close Rikers Island as a costly, unjust, ineffective and deteriorating relic of an outdated system. Advocates argue for replacing Rikers with jails in each of the city’s five boroughs, where they would be more convenient for court hearings and family visits, though such a transformation depends first on an overall reduction in the number of people the city incarcerates.

“The larger piece is we need to make Rikers no longer necessary,” the Rev. Winnie Varghese, the church’s director of justice and reconciliation, told Episcopal News Service in an interview.

That was an underlying recommendation of a 2017 report issued by the Independent Commission on New York City Criminal Justice and Incarceration Reform, whose work received financial support from a dozen philanthropic organizations, including Trinity Wall Street.

“Research shows that incarceration begets incarceration,” the commission’s report said. “Spending time behind bars also begets other problems, including eviction, unemployment, and family dysfunction. These burdens fall disproportionately on communities of color.”

The commission set a target of reducing the city’s jail population to 5,000 in a decade, which would mark a dramatic turnaround from a peak of more than 20,000 people behind bars in New York in the early 1980s.

Most of that reduction would be achieved by bail reforms, by changing the way the city holds suspects who are accused of crimes but not yet convicted. Pretrial detainees make up three of every four people incarcerated in the city.

Advocates for bail reform argue that many of those pretrial detainees remain at Rikers Island simply because they are too poor to pay their bail, not because they have been accused of a serious crime or are a significant danger to the public. Bail’s purpose, they point out, is merely to ensure that a defendant will appear in court for a hearing, or else the defendant risks forfeiting that money.

“What this system has turned into is a way to keep poor people in jail because they cannot afford bail,” Jonathan Lippman, a former state chief judge who chairs the reform commission, told Varghese in a video interview produced by Trinity Wall Street.

Lippman advocates eliminating cash bail altogether as one safeguard against unnecessary detentions, which often do more damage than good, he said. Simply spending a day or two at Rikers can have a profound effect on a detainee, and taken to extremes, it can ruin lives, as Lippman noted with the example of Kalief Browder.

Browder, accused of stealing a backpack in 2010 at age 16, was arrested and held at Rikers for three years, much of that time spent in solitary confinement, because his family was unable to afford his bail. He was never tried or convicted, and after he finally was released, he hanged himself at age 22. Last month, New York agreed to pay Browder’s family $3.3 million in a settlement over the young man’s detention.

“What a waste of a human being,” Lippman said. “This was a trifecta of everything that’s wrong with the criminal justice system.” Browder, Lippman explained, was a child charged as an adult, suffered through extended delays in his case and was not able to immediately return to his family because of a flawed bail system.

The Rev. Winnie Varghese of Trinity Church Wall Street interviews Jonathan Lippman, former New York State chief judge, about bail reform. Photo: Trinity Wall Street, from video

Mass incarceration has been called “The New Jim Crow” by Michelle Alexander in her book of that name, which likens it to slavery and segregation as another race-based caste system. In 2015, General Convention passed a resolution that encouraged Episcopalians to read Alexander’s book.

Also in 2015, General Convention took a detailed position against mass incarceration in another resolution that acknowledged “implicit racial bias and racial profiling result in a criminal justice system that disproportionately incarcerates people of color” and challenged the church “at every level to commit mindfully and intentionally to dismantling our current mass incarceration system.”

The resolution also urges reform of bail bond systems, “which rely upon often-unlicensed and unregulated bail bond agents and on conditioning release from pretrial incarceration solely on the ability to pay.”

New York isn’t the only state facing pressure to reform its bail laws. Last year, California became the first state to eliminate cash bail for suspects awaiting trial, though critics of that reform legislation argued the new law “actually undermines genuine criminal justice reform” because of its use of an algorithm to determine when suspects should be detained or released.

New Jersey, though not eliminating all cash bail, greatly limited its application through a law that took effect in January 2017. Crime rates appear to have plummeted in the two years since then, WNYC reported, though it wasn’t clear if the bail reform was the reason. The law’s lasting effects are still up for debate.

Those states’ laws and other examples around the country are helping to guide the work of reform in New York, Varghese said. “Frankly, we’re learning from other places,” she said, and she expressed optimism about the bail reforms offered by Gov. Andrew Cuomo in his state budget proposal last month.

Cuomo’s legislation calls for an end to cash bail and a significant reduction in the number of suspects held in jail awaiting trial. The legislation also would require police to rely on tickets rather than arrests for low-level crimes, though prosecutors could request a hearing to determine whether a suspect is too much of a threat to be released while a case is pending.

The Episcopal Church and other Christian denominations can add a powerful voice to such debates, Varghese said.

“I think churches have language around the morality of holding a person, taking the freedom of a person who has not been convicted of anything,” Varghese said. The Episcopal Church, especially given its vocal support of anti-poverty initiatives, “can bring some real moral weight.”

Varghese personally participated in the Mass Bail Out. Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights launched the campaign in early October to pay bail for female and teenage suspects held in Rikers, both as a direct action that would reduce the jail population there and as way to drawn attention to the cause of bail reform and closing the facility.

Organizers raised money from different donors to pay the bails. The role of volunteers like Varghese was to go to corrections offices, fill out paperwork and turn over a check to release the suspects. Varghese declined to provide to ENS any identifying information about the person she helped bail out other than to say it was a woman being held at Rose M. Singer Center on Rikers for a small-time charge, equivalent to shoplifting.

“We want to show them that the faith community supports them,” Varghese said. “One night at Rikers Island can change your life for the worse.”

About $1.2 million in bail was posted during the campaign, freeing 105 people with bails ranging from $700 to $100,000, according to a New York Times report on the results. City officials initially raised safety concerns when the Mass Bail Out was announced, though only two of the suspects released through the campaign had failed to appear at their subsequent court hearings as of mid-November.

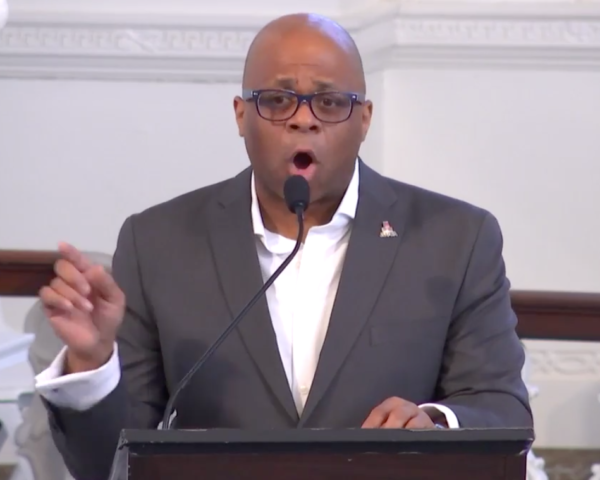

Varghese and Lippman spoke Jan. 31 at a breakfast forum on bail reform hosted by Trinity Wall Street. The event also featured several local and state lawmakers, though the human face of the problem was embodied early in the session by Marvin Mayfield, a reform advocate who spoke of his own experiences with the criminal justice system.

“I’ve been a victim of far more serious crimes in police custody than anything I’ve ever been arrested for,” Mayfield told the audience at the forum, video of which was posted online by Trinity Wall Street.

Marvin Mayfield, a bail reform advocate, speaks Jan. 31 at a breakfast forum hosted by Trinity Church Wall Street. Photo: Trinity Wall Street, via video

Mayfield spoke of being arrested a few years ago on suspicion of burglary and spending four months at Rikers Island because he didn’t have $10,000 to pay his bail. While there, he said, he was repeatedly assaulted by other detainees, who at one point broken his leg. He finally took a plea deal to end his ordeal.

“The system of money bail has not changed and is still disproportionately affecting the black and brown men and women of this state,” Mayfield said.

About 25,000 people are being held in jails across New York State each day, and Mayfield argued bail laws are a large factor in the injustices many of those people suffer while they are locked up.

“We must tell how [the laws are] hurting us,” Mayfield said. “We’ve all heard about the viciousness, the inhumanity, the brutality, the apathy, that exists in our county jails, but until you’ve lived it, you can’t appreciate the true impact of having your freedom taken away and being tossed into a violent and hostile environment.

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu