Pilgrimage to new ‘lynching memorial’ fosters racial understandingPosted Aug 29, 2018 |

|

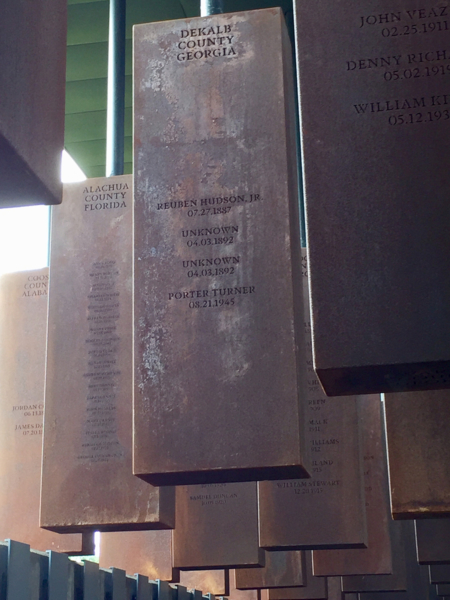

This April 28, 2018, photo shows pillars inscribed with the names of victims of lynching from Southern states hang from the ceilings inside the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Photo: Evan Frost/AP

[Episcopal News Service — Montgomery, Alabama] A spiritual pilgrimage can lay bare old scars, change who you are and how you see other people. That’s what many members of St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church in Atlanta reported after experiencing the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the collective story of more than 4,400 people who were lynched in this country.

These 82 travelers also stopped at the Legacy Museum nearby, which connects slavery and racial terrorism to mass incarceration in the United States. Their long-planned journey followed last month’s General Convention support for “Becoming Beloved Community,” the Episcopal Church’s interrelated resources for responding to racial injustice and organizing for reconciliation and healing. The convention passed resolutions tied to racial reconciliation, which is among the church’s three main priorities.

“I don’t think anything can fully prepare one for the atrocity that is part of our history,” the Rev. Angela Shepherd, St. Bartholomew’s rector, preached on Aug. 26, the morning after the pilgrimage, as participants continued to process the reality that between 1877 and 1950 more than 4,400 African-American men, women, and children were hanged, burned alive, shot, drowned or beaten to death by white mobs.

Facing that history, she and the pilgrimage participants believe, is a critical first step to countering the racial injustices embedded in our society today. Building this bridge is important at St. Bartholomew’s, which in April called Shepherd as its first female rector and first African-American rector. Located in DeKalb County, a fast-growing refugee and non-English speaking county that includes part of the city of Atlanta, St. Bartholomew’s 2017 profile described its membership as 96 percent white.

“We long for a more racially and ethnically diverse community, but have not yet made the necessary changes for that community to flourish,” the profile stated. “We are seeking new strategies.”

Barriers to the destination

This marker for DeKalb County, Georgia, in which St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church is located, indicates that the most recent lynching happened less than a decade before the church opened its doors. Photo: Virginia Murray

Despite careful planning for the 340-mile round trip journey, the group from St. Bartholomew’s encountered barriers that for many symbolized the profound discomfort of spiritual change.

The departure was delayed while the chartered bus service located an approved driver. Near Tuskegee, Alabama, the bus broke down in the summer heat. Its replacement was a shuttle full of items belonging to another tour group. Transformation apparently had its own itinerary.

The three-hour delay extended the travelers’ time for considering the history of racial violence along the Interstate 85 route, as researched and shared by trip organizers. Near the Newnan, Georgia, exit, the 1899 lynching of Sam Hose drew trainloads of Atlanta spectators who watched his burning and mutilation, with parts of his body taken as souvenirs. Near Lanett, Alabama, in 1912, four African-Americans were shot 300 times and left strung up beside a baptismal font outside a church.

Deaths by mob violence recall the crucifixion of Christ, a connection that the group had explored this summer by reading and discussing “The Cross and the Lynching Tree” by black liberation theologian James H. Cone.

As the travelers reached their destination, Shepherd read from the book’s closing exhortation, that Christians grasp the cross and lynching tree as blueprints for racial reconciliation.

“We were made brothers and sisters by the blood of the lynching tree, the blood of sexual union, and the blood of the cross of Jesus,” she read. “No gulf between blacks and whites is too great to overcome, for our beauty is more enduring than our brutality.”

Personal stories intertwine with past violence

Our common humanity was a message that gained momentum at the stark national memorial. No selfies are allowed, and the coffin-sized, rusting metal sculptures — each representing a county in which lynching occurred, and stenciled with the names of those executed — are meant to inspire individual and communal commitment to a just and peaceful future.

“Your names were never lost, each name a holy word,” Elizabeth Alexander wrote in her poem “Invocation” posted at the memorial.

The six-acre memorial grew out of the conviction that lynching was the single most powerful way that Americans enforced racial inequalities after slavery ended. This sanctioned violence spurred the exodus of 6 million African-Americans (the Great Migration) that indelibly changed the United States economically, physically, demographically, spiritually.

The country’s first national memorial acknowledging victims of racial terror lynchings is based on research by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), led by Bryan Stevenson, a visionary public interest attorney, bestselling memoirist (“Just Mercy”) and MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Grant recipient. Stevenson has said that this work is driven by his Christian faith, nurtured in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

For some in the mostly white St. Bartholomew’s group, the memorial sculptures summoned personal history. Nora Robillard found 10 names inscribed on the one for Clarke County, Mississippi, “That’s where I was born,” she remarked.

Juliana Lancaster recognized a surname on the Spalding County, Georgia, memorial. “I think I found a relative,” she said.

“Fifteen unknown people in Texas died on my birthdate,” said Loren Williams. “I can’t believe I will celebrate another birthday without thinking about that.”

Meanwhile, Shepherd discovered familiar names on memorials for the counties in Kentucky and Tennessee where her family is rooted.

In DeKalb County, Georgia, St Bartholomew’s established itself as a community leader in civil rights, AIDS outreach, LGBTQI issues, homelessness and other concerns starting in 1954. The memorial noted that the last of four lynchings documented in that county occurred in 1945.

“‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past,’” said Williams, quoting William Faulkner.

“The fact that we went as a church, a community of faith, amplified, almost prism-like, the ferocity of getting as close as we possibly could to the evil reality of lynching,” trip organizer Scotty Greene added. “Our shared faith in Christ got us down that road to do that. For me, this pilgrimage was functioning as Ken Wilber described religion: ‘not a conventional bolstering of consciousness but a radical transmutation and transformation at the deepest seat of consciousness itself.’ As another pilgrim shared with me, I’ll never be the same.”

The August light amid these hanging memorials to lynching victims creates a strong sense of the sacred, almost like being in church. Photo: John Agel

The memorial hinted at Christianity’s influence in the lives of victims and perpetrators. Biblical names dotted the sculptures: Amos, Emanuel, Caleb, Luke, Solomon, Ephraim, Isaac, Moses, Simon, Elijah, Abraham, Samuel and Mary. A minister from Hernando County, Florida, Arthur St. Clair, was lynched in 1877 for performing an interracial wedding.

“I found myself with tears in my eyes as I thought about how some must have felt abandoned by the law or even by God,” said pilgrimage participant Alexander Escobar. “In response I found myself saying, ‘I care.’”

We are more than the worst thing we have ever done

At the Legacy Museum, built at the riverfront where slave trading businesses once outnumbered Montgomery’s churches, the travelers learned how the elaborate narrative of white supremacy allows racial terrorism to flourish as a social custom outside the law.

While faith in God enabled many African-Americans to endure inhumane treatment, their oppressors often saw their domination as a God-given right.

“Lord, how come me here?” is a lyric to a spiritual sung at the museum by holograms of actors depicting chained slaves. As slavery gave way to a legal system that metes out excessive punishment to African-Americans, a newspaper reported a 14-year-old African-American boy was sentenced in 1944 to die in South Carolina’s electric chair. Because the boy was too short for his head to reach the electrodes, guards used a Bible as a booster seat.

These truths created a fresh, searing awareness among those on the pilgrimage.

“The stunning justification that ‘the other’ is not really a human being — and therefore deserves slavery, lynching, unfair prosecution, segregation, languishing imprisonment, legal killing — brings home to me the objectification of human beings in our society,” said Marilyn Hughes. “It hurts in my heart and it hurts our nation. And yet, there is still love enough for forgiveness and healing. This was my learning.”

“This memorial shows us how our country’s original sins — economic cruelty, slavery and genocide — are eating away at our social fabric like cancers,” said Ray Gangarosa, a pilgrimage participant. “As we observe, in real time, these echoes from our sordid past eroding our democratic institutions and those of other nations around the world, God is making it crystal clear that there is no cure, no redemption, no salvation for these sins but total excision.”

Many faith groups seeking reconciliation in Montgomery

The memorial and museum have hosted more than 100,000 visitors since opening in April.

“We are especially thrilled to be seeing great interest from church groups and faith communities, thousands of whom have already visited the sites,” said Sia Sanneh, an attorney with the Equal Justice Institute, in an email response for this story. “It has been moving to see so many faith groups honoring the lives lost during the era of racial terror, and we are also seeing faith groups interested both in confronting this difficult history and in better understanding the links between the history of racial injustice and our contemporary challenges.”

Pilgrimages like this demonstrate that “the work of racial healing and reconciliation in the church will be done most effectively at the parish level,” said Catherine Meeks, founding executive director of the Absalom Jones Episcopal Center for Racial Healing in Atlanta. “It delights me to see a parish taking the initiative to do this work, and I am deeply grateful to the Rev. Dr. Angela Shepherd and the St. Bartholomew pilgrims for making this important trip.”

In downtown Montgomery, the pilgrimage rested at St. John’s Episcopal Church, where the Rev. Robert C. Wisnewski Jr., rector (in light blue shirt), explained its history as the home church of Confederacy president Jefferson Davis. Photo: Virginia Murray

St. John’s Episcopal Church in downtown Montgomery, known as the parish where Confederacy president Jefferson Davis worshipped, has hosted several groups in conjunction with their visits to the memorial and museum. St. Bartholomew’s was the latest one.

Its rector, the Rev. Robert C. Wisnewski Jr., related how Episcopalians of Montgomery built the church and installed a spectacular Tiffany stained glass window. Tourists enjoy seeing the Jefferson Davis Pew, architecture and history.

Wealth, in Montgomery and other cities across the Southern states, was acquired through free slave labor and protected by Jim Crow laws.

“I loved looking at the beautiful decor, but it reminded me of how easy it is to be lulled into ignoring the ugly foundation of our privilege,” said Virginia Murray of St. Bartholomew’s. “The rector’s informal talk to us also demonstrated the challenges the Episcopal Church has, to make a place for Episcopalians on all stages of the reconciliation process. Although my church building was erected after slavery ended, I am still voluntarily a member of a denomination that was complicit in slavery, lynching, etc.”

The pilgrimage’s return bus trip included a closing liturgy, partly drawn from “Seeing the Face of God in Each Other: Antiracism Training Manual” and led by the Rev. Beverley Elliott, St. Bartholomew’s senior associate for pastoral care and adult formation and learning.

“The old satanic foe of racism is still woven into the fabric of our lives,” she read.

“Although, without you, we are not equal to this foe, through your grace empower us to overcome the forces that break community,” the travelers answered.

“You have created us as your own family. You have called us together,” she said. “The time is now for new beginnings.”

“May we do the work we must do in your church and world, while it is still day, before it is too late,” the travelers responded. “May we never tire, nor turn our back, nor believe our work is ever done. For each day we must begin anew.”

— Michelle Hiskey is an Atlanta-based freelance writer and member of St. Bartholomew’s Episcopal Church.

Social Menu