Episcopalians bring faith perspectives to Congress on both sides of political aislePosted Nov 9, 2017 |

|

The Episcopal Church’s Office of Government Relations counts 40 Episcopal members of the current Congress. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service – Washington, D.C.] One is the great-great-grandson of an Episcopal bishop. One grew up across the street from Virginia Theological Seminary. One made his first visit to the nation’s capital as a young chorister singing at Washington National Cathedral.

They all have at least one thing in common, in addition to their Episcopal faith: They now are among the 535 citizens serving as senators and representatives in Congress.

The United States has a long history of political leaders from the Anglican tradition, starting with President George Washington and many members of first Congress in 1789. The Episcopal Church’s prominence on Capitol Hill has been eclipsed by other denominations as the country has diversified over more than two centuries, though dozens of members of Congress still identify as Episcopalians or Anglicans.

“Being raised in the Episcopal Church, which is such an outwardly looking, active-faith community … we tend to be called to try and make a difference,” Rep. Andy Barr, R-Kentucky, told Episcopal News Service in an interview at his Capitol Hill office. “And there’s no other reason to run for public office than to want to make a difference.”

ENS interviewed several Episcopalians who serve in Congress to report on the range of ways faith influences lawmakers’ public service. For some, that faith is expressed openly at weekly prayer breakfasts and occasionally in policy speeches. Such public expressions of faith, though, often are tempered by the lawmakers’ awareness of the United States’ constitutional protections regarding religious freedom.

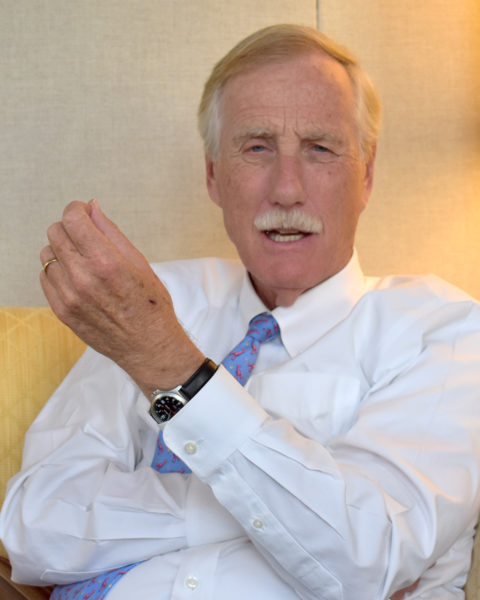

Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, speaks during an interview at his Capitol Hill office. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

“How do you apply your faith in your political life without imposing your faith on other people? That’s a challenge. That’s a dilemma,” Sen. Angus King, I-Maine, said while speaking with ENS in his office. “My faith is important to me. I use it as a guide in my decision-making, but I don’t feel it is appropriate for me to tell other people what their beliefs should be. And that’s a constant tension.”

The Episcopal Church also has a presence in Washington through its Office of Government Relations, which monitors legislation, coordinates with partner agencies and denominations, develops relationships with lawmakers and encourages Episcopalians’ activism through its Episcopal Public Policy Network.

That work focuses on areas the church has identified as “being an integral part of Christian calling and witness,” Office of Government Relations Director Rebecca Blachly said in an emailed statement.

“Given the impact of the federal government on issues such as homelessness, poverty, healthcare, as well as in the international context and for our Anglican Communion partners, we undertake important public witness for the most vulnerable,” Blachly said.

King is a longtime independent who caucuses with Democrats in Congress. When talking faith on Capitol Hill, he believes in humility.

“There always has to be a little shred of doubt in your faith,” King said, adding it is no accident that the Nicene Creed begins with the words “we believe” rather than “we know.”

He spent his childhood in Alexandria, Virginia and lived for several years in the shadow of Virginia Theological Seminary. His mother was a lay leader in the Diocese of Virginia. His father served on the vestry of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church. As an adult, his law and business career took him to Maine, where he was first elected governor in 1994. He held that office for eight years and was elected U.S. senator in 2012.

He now regularly attends St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Brunswick, Maine, and once described himself to Maine Magazine as “the guy who sits in the back.”

“I don’t know how I got into that habit,” King told ENS. He cautioned against reading into that habit any spiritual significance.

If you were to categorize the churchgoing persona of Rep. Bradley Byrne, R-Alabama, it might be The Guy Who Wears a Coat and Tie.

Rep. Bradley Byrne, R-Alabama, spoke with ENS at the Capitol after speaking on the floor of the House. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

He typically attends Sunday worship at St. James Episcopal Church when he is home in Fairhope, Alabama, and when he is in Washington on a Sunday morning, you’re likely to find him at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Lafayette Square across from the White House. But in January, on the Sunday after President Donald Trump’s inauguration, he chose a smaller church by the Capitol because he thought it wouldn’t be as crowded.

“I went to this church in a coat and tie, and I got there and I looked around – I was the only person there with a coat and tie,” Byrne said in an interview at the Capitol. “This one gentleman came over across the room and sat right next to me, and he said, ‘Everybody’s trying to figure out who you are.’

“And when I told him, they couldn’t have been nicer. … I’ve sort of found that the good thing about being in the Episcopal Church, I can kind of alight in any Episcopal Church, some are conservative, some are liberal, some are high church, some are low church, and you kind of get that same warm, welcoming feeling.”

Episcopalians, a diverse delegation

The Episcopalians in Congress defy any uniform categorization. They’re just as likely to be Republican as Democrat, and they come from all corners of the country. Texas’ 5th District is represented by an Episcopalian, Rep. Jeb Hensarling, a Republican. Hailing from Oregon’s 5th District, Rep. Kurt Schrader is an Episcopalian and a Democrat.

Most of these senators and representatives are white men, though there also are several women, including a member of the Congressional Black Caucus, Rep. Frederica Wilson, a Democrat representing Florida’s 24th district. Some Episcopalians, like King, Barr and Byrne, have only been in Congress a few years. Rep. Louise Slaughter, a New York Democrat and an Episcopalian, has represented her Rochester-area district since 1981.

The Episcopal Church’s Office of Government Relations counts 40 Episcopal members of the current Congress. Roman Catholics represent the largest group of lawmakers, with 168, followed by Baptists at 72, according to Pew Research Center analysis.

Faith on the Hill: The religious composition of the 115th Congress https://t.co/VMpuNwGcL3 pic.twitter.com/LrSK9KO6kk

— Pew Research Center (@pewresearch) January 8, 2017

Lawmakers may take their oath with a hand on the Bible, but they are sworn to uphold the Constitution. Each senator and representative brings a personal perspective on how – or whether – faith beliefs should influence public policy.

Byrne said he feels guided by “the sort of Anglican approach to understanding truth and what’s right and what’s wrong” – the “three-legged stool” of scripture, church traditions and individual reason or discernment.

“I’ve found that’s served me well throughout my life, before coming to Congress and in Congress,” Byrne said. “Scripture, tradition and reason are a big part of the way I approach things because that’s how I was brought up.”

Rep. Suzan DelBene, D-Washington, also credited her faith and the Episcopal Church with shaping her commitment to community service, “whether it was when I was a vestry member, a PTA mom, a Stephen Minister or serving in Congress.”

DelBene wasn’t available for a Capitol Hill interview but said in an emailed statement for this story that her public life is partly rooted in faith principles.

“I’ve always fought for those who need a helping hand because our communities are stronger when no one is left behind,” DelBene said. “Those driving principles continue to serve me in my current role in Congress and I’ll keep looking for ways to work across the aisle to ensure everyone can succeed.”

Barr credits his faith with introducing him to Washington, D.C., about 30 years ago. He was in sixth grade when he performed at National Cathedral with the choir from his church.

That experience played only an indirect role in calling him to public service, but Barr feels directly influenced by his “thinking church,” which he says encourages an open mind.

“It’s a church that teaches the love and compassion and grace of Christ, but it’s also a church that is willing to take on the difficult task of discerning scripture and thinking through it,” he said. “That allows for people of a lot of different perspectives to be welcome in the Episcopal Church.”

That wide spectrum includes some lawmakers who downplay the active role of faith in political life.

“It’s not something that I affirmatively think about,” Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-Rhode Island, said in an interview with ENS in his office. He sees faith as part of his DNA rather than something to wear on his sleeve. “It’s not like, what should my faith principles say about this? It’s much more embedded than that.”

Limits on religion in politics

Whitehouse, whose ancestor, the Rt. Rev. Henry John Whitehouse, was a bishop of the Diocese of Illinois in the 19th century, attended Episcopal church services growing up and went to St. Paul’s School, an Episcopal college prep school in Concord, New Hampshire. He is still an Episcopalian but now prefers worshipping at Central Congregational Church in Providence, Rhode Island, when back in his district.

He also is wary of politicians injecting faith into the work of government, and that was part of his message in 2014 when he spoke at a lobby day event held by the Secular Coalition of America, an atheist group.

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-Rhode Island, met with ENS in his Capitol Hill office. Photo: Episcopal News Service

“People of faith can recognize and respect the views of people who do not have faith,” Whitehouse told ENS. “They are as welcome and important a part of the American experiment as people who hold divergent faiths. … They, too, are all God’s children.”

Whitehouse sees “a natural corrective” to religious overreach in Congress, because legislation that crosses that line will face a tougher time garnering enough support for passage. There are fewer checks on federal judges once they are seated, Whitehouse said. As a member of the Senate Judicial Committee, he thinks it is fair to ask court nominees about their faith to ensure it won’t eclipse the law in deciding cases.

The issue came up this fall in questioning of Trevor McFadden, a Trump nominee to a federal district court post. McFadden is a member of an Anglican congregation in Falls Church, Virginia, which formed after members of a Falls Church congregation left during a theological dispute. Whitehouse riled some conservative critics by asking McFadden whether he, despite his church’s beliefs, would uphold the Supreme Court’s decision allowing same-sex marriage. McFadden responded he would.

“He answered well, and I voted for him,” Whitehouse told ENS.

Byrne has sought to defend religious freedoms, too, but from the opposite side of the gay marriage issue. He was a co-sponsor of a bill in 2015 called the First Amendment Defense Act that would bar “discriminatory action” against people, such as business owners, who follow religious convictions that gay marriage is wrong. The bill never made it out of committee.

“For us to tell somebody you can’t act out your faith in the way you conduct your business, I think that’s antithetical to the First Amendment,” Byrne said.

Such a stance may be in line with many of Byrne’s constituents, though it puts him at odds with the Episcopal Church, which just last month spoke out on the side of a gay couple who were denied a wedding cake by a Colorado cake shop. That legal case is now before the Supreme Court.

The Episcopal Church regularly takes values-based public stances on public issues, including through the Office of Government Relations’ advocacy in Washington.

“All of our advocacy is based on General Convention resolutions and thus reflects the will of the Church,” Blachly said, while stressing that her office takes a nonpartisan approach.

“We know that Episcopalians in the pews also have a diversity of political opinions, and we realize it is possible to have different views on the best way to achieve a more just and compassionate world,” she said. “Bipartisanship, as well as respectful listening and dialogue, is central to all of our engagement as we build relationships with members of Congress, the administration and federal departments and agencies.”

Sometimes Episcopalians in Congress are closely aligned with their church on certain issues, as Whitehouse is on climate change. That and ocean quality are important in his coastal state, while the Episcopal Church has promoted environmental stewardship for decades. The House of Bishops also made environmental justice one of the themes of its September meeting in Alaska.

“God has made nature pretty resilient if she’s only given a chance, and the oceans are perhaps the most spectacularly resilient of all,” Whitehouse said. “But they’ve got to be given that chance.”

Differing on issues, united by faith

On some issues, however, the church may find itself in the middle of a partisan divide. The Trump administration’s pursuit of greater restrictions on refugee resettlement sparked opposition this year from the Episcopal Church, whose Episcopal Migration Ministries is one of nine organizations that facilitate that resettlement on behalf of the State Department.

A policy alert issued in October by the Office of Government Relations warned of “devastating consequences for refugees” who are barred from entering the United States.

Republicans have generally been more supportive of the president’s refugee policies. Both Byrne and Barr spoke in favor of the refugee resettlement program while citing national security as a legitimate reason to tighten the process, at least temporarily.

Rep. Andy Barr, R-Kentucky, speaks about his faith as an Episcopalian in his office in Washington. Photo: David Paulsen/Episcopal News Service

Such a policy position doesn’t necessarily contradict the church, Barr said.

“We may come at the issue of refugees or immigrants differently and we may have some disagreements,” Barr said, “but I think all of us in Congress who are Episcopalians, we believe that this country is a nation of immigrants. … We believe in the duty and the obligation of our country to offer refuge and asylum to the politically and religiously oppressed.”

Faith also can provide common ground, a bridge across the partisan divide. King regularly attends the Senate’s weekly interfaith prayer breakfast, “the only bipartisan event around here.” Only senators are invited, and 20 or more typically attend any given Wednesday morning in a room at the Capitol.

“It’s my favorite hour of the week,” King said. The event is a chance to get to know his fellow senators, Republicans and Democrats, as real people rather than political opponents, and he frequently learns something new about them.

Byrne, too, sees faith as “a force for unity” and often attends House prayer group meetings that draw members of both parties.

His religion became an issue in the 2016 election, when a Republican rival who is Baptist tried to argue Byrne, as an Episcopalian, wasn’t conservative enough for his Alabama district. That line of attack didn’t gain much traction, Byrne said.

“I’m not going to back down from the fact I came to Christ through the Episcopal Church. The Episcopal Church continues to feed me day to day, week to week, month to month,” he told ENS. “And the other people of faith in my district, particularly those that know me, respect me for that.”

– David Paulsen is an editor and reporter for the Episcopal News Service. He can be reached at dpaulsen@episcopalchurch.org.

Social Menu