This New York priest is on a mission to help children trapped in sex trafficking at hotelsHotel-sized soaps labeled with a toll-free hotline can help.Posted Sep 21, 2017 |

|

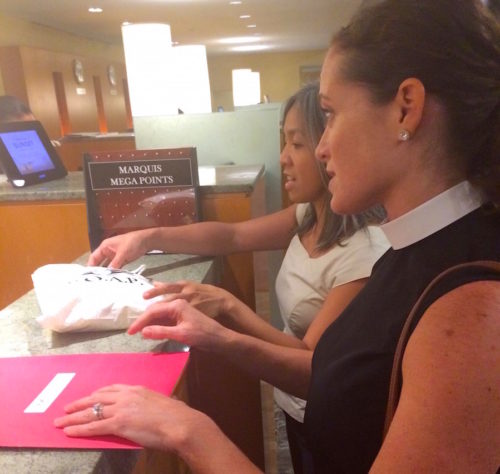

Parishioner and volunteer Nathalie Abejero and the Rev. Adrian Dannhauser, associate rector of Church of the Incarnation in New York, tell a hotel desk clerk at New York Marriott Marquis about the Saving Our Adolescents from Prostitution (S.O.A.P.) Project, asking that staff use soaps labeled with a toll-free help hotline for sex-trafficking victims. Photo: Amy Sowder

[Episcopal News Service] She strode through midtown Manhattan with purpose, her black tote bag held close as she dropped a dollar into the jangling coffee can of a street person stationed on a corner.

Weaving around the city sidewalks in her flowered pencil skirt, black flats and black tank with a clerical collar, the Rev. Adrian Dannhauser had four destinations on her list that evening — all upscale hotels where she hopes her efforts make a dent in revealing the horrific secret right under everyone’s noses.

Child sex trafficking happens at pretty much every hotel, whether it’s glitzy or seedy, Dannhauser and survivors say. The average age a child is forced into prostitution is 13. Human trafficking, for labor or sex, is the second-leading crime in the world, including the United States, according to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF). And one in three children is solicited for sex within 48 hours of running away or becoming homeless.

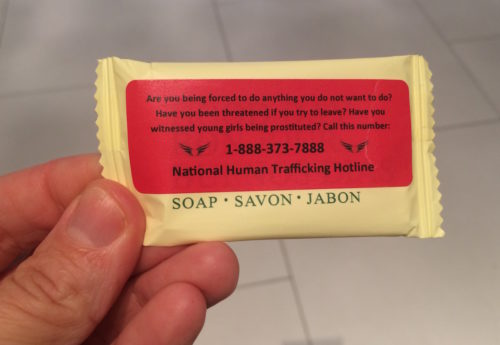

A mother of a daughter who’s almost 9, Dannhauser wants every hotel employee to be trained to recognize the signs and know what to do about it. She wants the children, usually girls, forced by threats, violence and drugs to have sex with countless men behind the hotel room doors, to find a soap in the hotel bathroom with a sticker on the wrapper providing a toll-free hotline to call for help.

“We’re ‘soaping up’ midtown,” Dannhauser said as she led the way to the next hotel, carrying bags that each contained 100 hotel-sized labeled soaps and folders full of information. “I’ve talked to hotel staff who said they did see something ‘off’ and didn’t know what to do.”

The Rev. Adrian Dannhauser, associate rector of Church of the Incarnation in New York, asks an employee at Fairfield Inn & Suites in New York whether he’s had training to spot and report sex-trafficking victims. She’s leading a committee at her church, as well as a diocesan task force, to help the victims escape and to spread awareness of the problem, which is rampant in the travel and tourism industry nationwide. Photo: Amy Sowder

The associate rector of Church of the Incarnation on Madison Avenue brought along parishioner Nathalie Abejero, also a mother, for the hotel visits. They, along with the rest of her parish’s anti-trafficking committee of seven to 10 people, have visited close to 40 hotels in the past year.

“It’s so widespread. It could be anyone: the nicest, sweetest neighbor of yours who you’d never guess,” Abejero said as she waited in the lobby of New York Marriott Marquis in the heart of Times Square.

“It’s so sick,” Abejero said a moment before the pair approached the hotel’s check-in clerks.

Dannhauser is the chairperson of the Diocese of New York’s Task Force Against Human Trafficking. She was recently selected as a New York Nonprofit Media 40 Under 40 Rising Stars honoree for her work to combat human trafficking.

Why hotels and motels are ideal targets

The majority of trafficking happens at hotels and motels, according to Polaris Project, a Washington D.C.-based organization dedicated to eradicating modern slavery globally.

Unlike other venues, hotels and motels allow traffickers some anonymity. Traffickers can pay for rooms in cash and change locations easily, which makes it easier to avoid detection than using an apartment, car or legitimate business front, all of which are traceable back to the owners.

The biggest problem is lack of awareness. Hotel staff and guests don’t realize that trafficking is happening, or how to recognize the signs. Even if they do sense that a situation is suspicious, they may not know how to report it or whether it’s worth reporting at all.

There are two clear ways to draw the line between prostitution and sex trafficking. If a person under 18 is involved in commercial sex, he or she is being trafficked. Also, anyone 18 and older with a pimp is being trafficked.

“Trafficking is lack of choice. Slavery is lack of choice,” Dannhauser said. “Obviously, with children, it pulls your heartstrings more.”

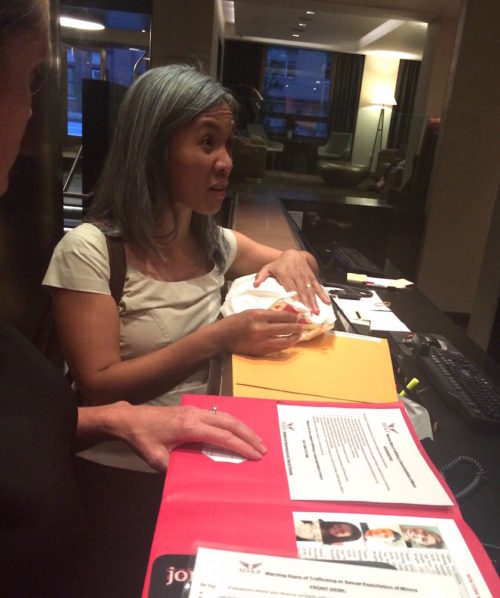

Volunteer Nathalie Abejero tells a hotel check-in clerk at New York Marriott Marquis about the Saving Our Adolescents from Prostitution (S.O.A.P.) Project, asking that staff place into the housekeeping carts the special soaps labeled with a toll-free help hotline for sex-trafficking victims. Photo: Amy Sowder

Online shopping for underage sex

Traffickers also use the internet. Children are more expensive and are most often purchased in the adult or dating sections of classified advertising websites, such as Backpage.com, which sells everything from boats to Beanie Babies. It is second in popularity only to Craigslist. When the woman’s face isn’t photographed, it’s often a girl younger than 18. A recent U.S. Senate report said the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children states that 73 percent of all child trafficking reports it receives involve Backpage.

Using a defense of freedom of expression from government censorship and being “merely a host of content created by others and therefore immune from liability under the Communications Decency Act,” the site has been embroiled in legal battles, from criminal charges against its founders and CEO, to politicians’ efforts to modify the federal law.

Between 2010 and 2015, the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children reported an 846 percent increase in suspected child sex trafficking, much of it online.

A priest’s calling for advocacy

Dannhauser’s work is needed now more than ever.

A former bankruptcy attorney, Dannhauser has no personal connection to this horrifying criminal epidemic, but during her contemplative prayer practice while in seminary, she felt a call from God to pursue this mission.

She was resistant at first, but she felt compelled by the Holy Spirit to consider this cause.

“It’s all about using the voice we have for the voiceless,” Dannhauser said. “Churches are good about service, but I don’t know that we always get the advocacy piece. I find this so energizing.”

After Dannhauser’s committee worked on contacting hotels in the metropolitan area for almost a year, the group joined forces with the S.O.A.P. (Save Our Adolescents from Prostitution) Project in the summer of 2017.

Volunteers stick labels onto hotel-sized soaps at the S.O.A.P. labeling party in July at Church of the Incarnation in New York. They’re working to spread awareness of child sex trafficking in hotels, and help the victims get out. Photo: Church of the Incarnation

In July, the committee had a S.O.A.P. labeling party, during which they stuck labels onto 2,000 bars of soap that provide a toll-free help hotline for victims to call. They deliver those soaps to the hotels along with a packet of other information, including a missing children’s page, a warning signs list and a hotline mouse pad.

A survivor’s tale

Anneke Lucas participated in the New York church’s labeling party and told her story, as well.

Raised in Belgium, Lucas was sold by her parents to an exclusive sex-trafficking ring for wealthy politicians when she was 6, according to a “Real Women Real Stories” video on the Living Resistance website. For more than five years, she was raped and tortured. At puberty, she was in danger of being murdered, but she got out just in time.

Today, Lucas is a mother and leader of an organization that brings yoga to prisons. Lucas, Dannhauser and other leaders advocating for trafficking victims are pushing for legislation to be passed to protect children.

Anneke Lucas, a child trafficking survivor who is now a mother and leader of a group that brings yoga into prisons, told her story at the S.O.A.P. labeling party at Church of the Incarnation in New York. Photo: Church of the Incarnation

Connecticut passed a groundbreaking piece of legislation — the first of its kind in the United States — requiring hotels and motels to post signs in a visible place spelling out what trafficking is. The notice must also contain information on how to get help by contacting the National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline.

The law also requires all hotel and motel staff in the state to receive training on how to recognize victims and activities commonly associated with human trafficking.

“A law like this could help children who are trafficked in New York,” Lucas said in the video. A tiny hotel soap with a red label could be a trapped child’s saving grace. “I would have found a way to call the hotline, had I seen a notice,” she said.

The S.O.A.P. Project

Founded by Theresa Flores in Ohio, the S.O.A.P. Project is specifically focused on educating and increasing public awareness of the prevalence of human trafficking, in order to help trafficked survivors heal and also to prevent more teens from being victimized this way in the United States. Eighty percent of trafficked victims are women, and half are children, she said.

S.O.A.P. representatives travel all over the United States to hold outreach workshops during large public events. The nonprofit organization partners with local groups to distribute millions of bars of soap wrapped with a red band that gives the National Human Trafficking Hotline number — 1 (888) 373-7888 — and resources to high-risk motels and hotels.

Based in Ohio, the nonprofit S.O.A.P. Project helps local volunteer groups label soaps with a toll-free help hotline and trains the volunteers to contact hotels and spread awareness of child sex trafficking in the United States. Photo: Amy Sowder

Trained volunteers such as Dannhauser and Abejero offer the soap free of charge to hotels and motels, along with training to be able to identify and report sex trafficking when they see it in their establishments.

An author and advocate, Flores, 52, is also a survivor of child sex trafficking.

She came from a good Roman Catholic home with two parents and no abuse. She was taught to be abstinent until marriage. But when she was 15, a boy in school drugged her and raped her, and his cousins took photos. The boy threatened to post the photos all over school, at her church and at her father’s office if she didn’t “work” to get each photo back.

Flores was so ashamed of what had happened to her that she didn’t tell anyone. She found herself being called in the middle of the night and driven to mansions where she was forced to have sex with old men. They didn’t know her name or even ask, except for one man, who seemed to not know she was underage. Her pimp rebuked him, saying “she has no name.”

She remembers being kidnapped, drugged and beaten, taken far away to Detroit and pulled out of the car by her hair to an open hotel where 20 men waited for her. She was 16 by then, in a sea of men, auctioned off to highest bidder, over and over until she passed out.

“Nobody knew this was going on to a kid like me,” Flores said in her TEDx Talk.

Her story is an example of how a child from any background, race or socio-economic status can become trapped in sex trafficking. These days, most people find prostitutes online, not by looking for streetwalkers, Flores said.

“It’s basically fear,” Flores told Episcopal News Service. “These women are terrified and are being beaten and are threatened by the pimp, who is the trafficker. They tell you they know where your family is and get you addicted to drugs. They all use these tactics.”

In these disgusting, deplorable situations, it’s almost guaranteed a trafficking victim will reach for the hotel room’s bar of soap. “That darkest moment is in those hotels, but they all go into the bathroom to clean up afterwards,” she said.

That’s how the idea hatched to use soap as the way to reach the trafficked victims. If hotel managers don’t agree to place a labeled soap in each hotel room bathroom, volunteers suggest that they keep the soaps on the housekeeping carts for cleaning employees to place in the bathroom when they notice the signs.

The signs include some obvious clues and some more subtle ones:

• A man is checking in with a much-younger female.

• A young woman looks a bit zonked out or bruised.

• A young woman has no identification proof.

• A hotel room is paid for in cash.

• A hotel room is purchased by the hour or by the day repeatedly, or for extended stays longer than usual.

• Several men are seen coming and going from one room.

• Many more towels are requested than is typical.

• Someone stands guard by the room door or is acting distrustful around security.

If you suspect sex trafficking, call the police, FBI or the National Hotline at 1-888-373-7888, or text: HELP to BeFree (233733). For more information, visit www.soapproject.org, www.traffickfree.com and www.ecpatusa.org.

Flores has given out close to a million soaps since she founded the organization more than six years ago.

She targets her hotel efforts during big events. The Super Bowl, NASCAR races, Republican and Democratic conventions, the Indianapolis 500, entertainment awards shows, the Kentucky Derby and the Detroit Auto Show are a few. When there’s likely to be a flood of people into town for a short time, especially when it’s mostly men, the demand will rise.

So, the supply follows.

Typically, in Detroit, there are 200 ads of women for sale on Backpage.com, Flores said. But the female ads spike to 500 to 600 during the Detroit Auto Show.

Advocacy within the Episcopal Church

Dannhauser wants to encourage this kind of advocacy work throughout the Episcopal Church at large.

The priest got the Episcopal Public Policy Network to send an action alert about any related legislation going through U.S. Congress so that more Episcopalians could get involved. The Episcopal network created its own human trafficking page chock full of helpful information, from advocacy updates from U.S. Congress and ongoing efforts by local Episcopal churches to ways to contact local elected officials and resources provided by the Episcopal Church and Anglican Communion.

Dannhauser was critical in helping to pass a series of resolutions at the Diocese of New York’s annual convention in November. The resolutions encourage the diocese to prioritize doing business with those hotels, travel agencies and airlines that have signed the Tourism Child-Protection Code of Conduct when traveling for church-related business. They also urge all parishes and individual Episcopalians to make those same choices in their business and personal travel.

“And if we used a hotel or airline that hadn’t signed onto this code, then we’d try to sign them up; we have a letter for this and you can chat with the general manager about this,” Dannhauser said. “Anybody can do that kind of thing.”

The Code, as it’s commonly called, was developed by End Child Prostitution and Trafficking (ECPAT-USA), a nonprofit organization based in Brooklyn, New York, and part of ECPAT International. It’s the only voluntary set of business principles travel and tour companies can implement to prevent child sex tourism and trafficking of children.

Those who sign The Code agree to establish a policy and procedures against sexual exploitation of children; train employees in children’s rights, the prevention of sexual exploitation and ways to report suspected cases; include a clause in contracts stating a zero-tolerance policy of sexual exploitation of children; provide information to travelers; and report annually on related activities.

Several large travel suppliers have signed The Code, including Hampton Hotels, Hilton Worldwide and Waldorf Astoria Hotels & Resorts, according to Business Travel News.

But while the heads of these hotel companies agree to this code, the training and education don’t always trickle down to every hotel location. That’s where efforts like those of Dannhauser’s committee come into play.

Dannhauser is excited that the diocese’s sign-up letter is accessible to anyone in the Episcopal Church, so congregations can share it and educate their own hotels and travel agencies. The letter is downloadable here.

She’s pressing to place a set of resolutions calling for the church to support the ECPAT code — similar to the New York diocesan resolutions — on the agenda at General Convention in the summer of 2018.

“I also plan to have the toolkit ready at that time — the one for parishes to use to do their own hotel outreach with hotels in their communities,” Dannhauser said.

How hotel staff respond

On this particular August evening, Dannhauser’s and Abejero’s second stop was at the 49-story marbled, modern New York Marriott Marquis in the heart of Times Square.

The Rev. Adrian Dannhauser, associate rector of Church of the Incarnation in New York, and parishioner and volunteer Nathalie Abejero head to the hotel check-in desks at New York Marriott Marquis to spread awareness of training available to spot and report child sex trafficking, which is common in all kinds of hotels. Photo: Amy Sowder

The manager-on-duty and two clerks at the hotel’s front desk were friendly and willing to discuss sex trafficking when the two women showed up unannounced. Hotel employees undergo sex trafficking training with a video every six months, they said.

“It’s something we’re actively on the lookout for,” the manager said.

Sometimes the volunteers can’t even get a manager to come out to speak to them; it’s hard to tell whether it’s because the manager is busy or just not interested. Most desk clerks and managers said they are aware of the problem and several of them had training by video. Others admitted they didn’t know what to do when they suspected something was awry.

They all took the soaps.

“It was a better response than I expected,” Abejero said.

— Amy Sowder is a special correspondent for the Episcopal News Service, and a writer and editor in Brooklyn, New York.

Editor’s note: Combatting human trafficking will be on the agenda during the Oct. 2-6 meetings of the moderators and primates (leaders) of the Anglican Communion’s 39 provinces. Archbishop Francisco de Assis da Silva, primate of the Igreja Episcopal Anglicana do Brasil, explains why here.

Social Menu