Historically black church explores faith and justice in gentrified Washington, D.C.Posted Jul 28, 2016 |

|

The Rev. Peter Jarrett-Schell, rector, and the Rev. Gayle Fisher-Stewart, associate rector, of Calvary Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., stand for a photo under a Black Lives Matter banner. Photo: Lynette Wilson

[Episcopal News Service – Washington, D.C.] The decision to display a Black Lives Matter banner above the parish hall entrance did not come easily for the leadership of Calvary Episcopal Church, a historically black church with a reputation for social justice and action on the U.S. capital’s northeast side.

“Some folks have taken offense to it … and I think some people really appreciate it,” said the Rev. Peter Jarrett-Schell, Calvary’s rector, during a recent interview with Episcopal News Service. The decision was “contentious” and “not unanimous,” he said. “It’s also been an opportunity for conversation.”

It’s not uncommon for Calvary to engage in discussions that challenge the congregation and the community to think and to act with an intention toward justice.

Calvary has initiated conversations – contentious, difficult, provocative and otherwise – over the last two years in particular. Church leaders began talking in earnest after the police shooting of Michael Brown in August 2014 and decided to host a community-wide forum, “Ferguson: Could It Happen Here?” The forum brought together church and community members, and law enforcement officials.

“It was a peaceable back-and-forth, that Ferguson can happen here given the right circumstances,” said the Rev. Gayle Fisher-Stewart, Calvary’s associate rector, and a 20-year, now retired, veteran of the D.C. Metropolitan Police. “We know that 90 percent of all civil disorders in this country have the police at their nexus; it doesn’t mean that the police caused it, but that the police were somehow involved, and it could be something fairly simple that blows up.”

The Ferguson conversation led Fisher-Stewart, newly ordained a priest last November, to create the Center for the Study of Faith in Justice at Calvary with the help of a grant from the Episcopal Evangelism Society. The grant has allowed the church to host forums focused on themes related to community involvement, race and social justice: police in the community; the black church; and white spaces off limits to blacks, among others. The latter two were workshops facilitated by the Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, the author of “Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God.”

“We realized here at Calvary that we are a black congregation in a predominately white denomination and we’ve kinda had this split personality going,” said Fisher-Stewart, adding that Brown Douglas helped Calvary to redefine its call.

“The black church was formed because of injustice. And so if we pick up that mantle again to do justice, which we find in the mission of Christ when he read from the scroll of Isaiah in the temple – it was about doing justice, it was about the least of these,” she said.

For example, the most recent forum focused on young black males, asking the question: Are they an endangered species?

“We had community organizers, activists, and psychologists, theologians, educators, to help us think about why young black males are endangered beyond the issue of policing, but also: What we are called to do to assist them in becoming the people God has called them to be?”

The “what” that God has called young black males to be is something of a focus for Brittany Livingston, a 26-year-old social worker who counsels primarily middle-school-aged African-American males at an all-boys parochial school.

“Most of our boys are young African-American males and it can be a challenge because I look at little brown faces every day and they often have real feelings about what’s going on,” said Livingston, adding that sometimes the violence and the overall situation makes her feel helpless. “But going in every day working with those little boys helps me. I’m working with them day-to-day and their lives matter day-to-day to me.”

Members and friends of Calvary Episcopal Church participated in a “Do Justice” silent march and prayer vigil for the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives 40th annual conference in Washington, D.C., on July 20. The action was organized by the Center for the Study of Faith in Justice at Calvary. Photo: Lynette Wilson

2016 has left many people feeling helpless. July has been a deadly month, both for policemen and black men in Louisiana, Minnesota and Texas. On Sunday, July 17, as members of Calvary left the church following the morning’s Eucharist, news broke of yet another deadly shooting in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, this time, a former Marine killed two policemen and a sheriff’s deputy. It was the “the juxtaposition of these deaths” that “forced the entire nation to stop and take notice,” as the Rev. Charles A. Wynder, a deacon and the Episcopal Church’s missioner for social justice and advocacy engagement, recently wrote in an essay for The Living Church.

Livingston, a lifelong member of Calvary, said having a place to come to talk about it helps.

“After every community forum or event that we do, something always comes out of it,” she said. “Whether it be someone coming up to you afterward and saying, ‘Hey, become a part of this mentoring program,’ or you see Rev. Gayle and my mom and the church going to protest somewhere, and then on Sundays we are praying about it, and Rev. Schell or Rev. Gayle will get up there and say something about it and so it kinda lifts that helpless feeling,” she said.

Livingston’s mother, Ellen Livingston, also a social worker and Calvary leader, has witnessed rhetoric around Black Lives Matter play out in the lives of the young people she works with as well. From the white adolescent girl from a mixed neighborhood whose peers are telling her, she doesn’t belong: “This young lady is trying to deal with something far greater than what she can imagine,” said Livingston. To the young black child who attends a predominantly white summer camp at a prestigious private school where he was targeted by white students: “ ‘So black lives matter,’ and he was being bullied, ‘your life doesn’t matter any more than mine, all our lives matter.’ ”

The Black Lives Matter movement, like the Center for the Study of Faith and Justice at Calvary, was born in 2013 out of tragedy, this time with the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the neighborhood watch coordinator who shot 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in a gated community just north of Orlando, Florida. The movement grew out of the Twitter hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, calling attention to police and vigilante violence against black Americans.

In making the decision to hang the “Black Lives Matter” banner, it came down to the church’s responsibility as a Christian congregation, said Jarrett-Schell.

“The Gospel declares that all lives matter, but in this moment right now we see in the eyes of the world and our society, not all lives matter equally and black lives are undervalued and that’s putting it mildly,” Jarrett-Schell said. “We as Christians if we truly believe that the Gospel brings good news for all people, and we look and we see that there’s a group of people in our immediate neighborhood and our society, particularly black people, who are not being treated as children of God, the way they should be, then we have to bear witness to that specifically.”

Calvary’s matriarch, a woman described as making space for everyone, initially opposed the Black Lives Matter banner out of concern for what people coming to the church would think. But after walking beneath it a few times, Jarrett-Schell said, she realized the banner says that her life matters and that if someone disagrees they don’t need to come to the church.

The Black Lives Matter movement follows the Occupy movement, another grassroots movement that began in New York in 2011, seeking social and economic equality. Just as Occupy took laid bare the worldwide problem of social and economic inequality, Black Lives has brought racism into everyday conversation.

“When we look at the problem (racism) in national and international terms, it just seems too big for us to do anything,” said Jarrett-Schell, when asked if some of the most significant change happens at the community level. “And when we look at history, these big turning points, these moments when the arc of history has actually bent toward justice, the apex moment, but we ignore the fact that there has always been years and years of grassroots community work that actually made the big national moment possible.”

An already tense presidential election has been made more tense as race relations linger in American’s minds; support for Black Lives Matter, an often-misunderstood movement, runs the spectrum. Yet violence against black Americans is nothing new. Nonblack Americans first saw it broadcast in their living rooms with the beating of Rodney King at the hands of Los Angeles police officers in 1991; it dominated the social commentary in the lyrics of early hip hop music. Smartphones equipped with video cameras have upped the frequency in which police violence has been documented and shared publicly.

The Los Angeles police chief called King’s beating an aberration, but the black community and law enforcement officials knew better.

“[We said] ‘the aberration’ was that it was caught on film because it happens every day in America,” said Fisher-Stewart, it’s just now that everyone has cell phones. “Now anyone can take out their phone and record what has been going on forever in terms of policing in America.

“The crisis has always been there; it’s ever-present now with technology.”

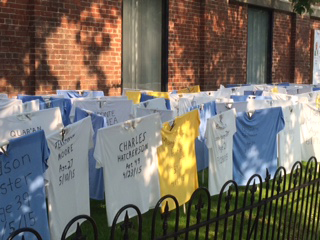

Calvary Episcopal Church hosted an exhibit of 200 T-shirts bearing the name, date of birth and date of death of victims of violence crime in the D.C.-metropolitan area. Photo: Gayle Fisher-Stewart

Long before the church decided to display the Black Lives Matter banner, they hosted an exhibit of more than 200 T-shirts bearing the name, date of birth and date of death of victims of violence crime in the D.C.-metropolitan area. The exhibit, organized by Heeding God’s Call, called on visitors to pray for each individual who had died. The church now is working on a new conversation series, ranging from youth and engaging with the police force to education beyond high school, entrepreneurship and male-female relationships.

It’s impossible to have a conversation about police violence and black males without the conversation eventually turning to racism, both cultural and institutional, marginalization and economic inequality. Moreover, forums and the conversations at Calvary are taking place under the backdrop of gentrification.

“We are a commuter church, our community is beginning to look nothing like it did when we were kids,” said Ellen Livingston, who grew up a 10- to 15-minute walk from the church and later moved to the suburbs. “This (church) was a community center at one time, and our community is changing, and the gentrification and the isolation and the marginalization of those who are black and have remained in the city, so we want to provide support for them, as well.”

Calvary Episcopal Church, a historically black church in Washington, D.C., is located on the city’s gentrified northeast side. Just down the block, at the corner of H Street and Sixth Street NE, Apollo Apartments, anchored by a Whole Foods Market, is under construction on the former site of the historic Apollo Theater. Photo: Lynette Wilson

Located one block off H Street, once the commercial heart of black Washington, D.C., a street that burned during the violent protests that followed the assassination of the Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, the church, established as a mission church in a storefront in 1901, now is faced with holding tight to its identity in a gentrified, rapidly changing neighborhood. Once referred to as the “Chocolate City,” the nation’s capital has gone from having a 70 percent African-American majority a generation ago to less than 50 percent black today.

“H Street was predominantly black, it was like the downtown for black folks, and it burned, the riots, it burned, just like some portions of Seventh Street, U Street burned, portions of it, the black areas of the city, were the ones that burned, and so it has taken a while for them to totally come back, and as they’ve come back, they’ve come back gentrified,” said Fisher-Stewart.

“We are like many of the historically black congregations in D.C. that are surrounded by people who don’t look like us, but we still need to reach out and spread the Gospel to them.”

The community’s gentrification is beginning to change the church’s mission. Every third Thursday of the month Calvary hosts a meeting to talk about community changes, such as a massive apartment building anchored by a Whole Foods Market under construction on the corner of northeast Sixth and H streets in what used to be the site the historic Apollo Theater. Other changes are less obvious to newcomers and visitors.

“I was driving in this morning – I was coming out West Virginia Avenue by Gallaudet University – and I noticed on the west side of the street where there used to be no sidewalk, just a pathway, there’s now a sidewalk there … that’s where I used to live, I used to live off West Virginia Avenue – there was never any sidewalk on that side of the street. You couldn’t walk on that side of the street unless you walked out in the street but now there’s a sidewalk there – and that’s 50 years,” said Kevin Douglas, a longtime member who grew up within walking distance of the church.

There’s no shortage of churches in the immediate neighborhood, nearby a tiny Christian storefront church on H Street identified only with a cross is surrounded by restaurants, juice bars, yoga studios and a boutique selling pet supplies. Calvary’s congregation skews older and female; the vibrant youth group, one of the largest African-American church youth groups in the city, of Brittany Livingston’s childhood, is long gone.

“As much as many of our members have moved away, all of our members have a great affection for this neighborhood, even as it is changing rapidly,” said Jarrett-Schell, who in 2012 became the church’s first white rector. “We are looking to be a congregation that shares the Good News of Christ in this particular place and in this particular neighborhood.

“We do have a lot of new families moving in and that is really complicated for Calvary … there’s opportunity there, but there is also a great deal of loss, displacement going on. So when we say share the Good News, obviously we are talking in spiritual and temporal terms, there’s a message of hope that the Gospel offers and we want the people in the neighborhood to hear it. There are expectations and social responsibilities that hope; we want the people of this neighborhood to hear about that as well, and we want Calvary to be a place that shares that.”

– Lynette Wilson is an editor/reporter for Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu