Out of Deep Waters: ‘Co-opted into a resurrection story’Posted Sep 2, 2015 |

|

[Episcopal News Service – Gulf Coast] In the 10 years since Hurricane Katrina changed the Gulf Coast forever, the arc of The Episcopal Church’s ministry here traces a story of evolution and transformation filled with lessons for the rest of the church.

It was clear that recovery along the Gulf Coast would take years and, 10 years later, The Episcopal Church serves communities in which the path to recovery has been rocky for some and smoother for others. In some places, including parts of New Orleans, the recovery is still incomplete and far from secure.

“The scars are there and, in some instances, deep pain continues to surface with not much help actually,” Diocese of Louisiana Bishop Morris Thompson told Episcopal News Service. “But for many people life has gone on in a new way.”

Katrina was directly responsible for approximately 1,300 deaths in Louisiana (the majority were people older than 60 years) and 200 in Mississippi. Including deaths indirectly related to the storm, an estimated 1,833 people died. Producing an estimated $151 billion in property damage, including $75 billion in the New Orleans area and along the Mississippi coast, Katrina was the costliest U.S. hurricane on record in terms of property loss.

After making landfall as a Category 1 storm in South Florida, Katrina made two more landfalls along the Gulf Coast, including its last, as a Category 3 storm at the mouth of the Pearl River along the Louisiana-Mississippi coast. Katrina remained at hurricane strength as far inland as Meridian, Mississippi, about 170 miles north of the storm’s last landfall. The hurricane obliterated entire Gulf Coast towns in Mississippi, but the devastation in New Orleans got far more media attention.

After making landfall as a Category 1 storm in South Florida, Katrina made two more landfalls along the Gulf Coast, including its last, as a Category 3 storm at the mouth of the Pearl River along the Louisiana-Mississippi coast. Katrina remained at hurricane strength as far inland as Meridian, Mississippi, about 170 miles north of the storm’s last landfall. The hurricane obliterated entire Gulf Coast towns in Mississippi, but the devastation in New Orleans got far more media attention.

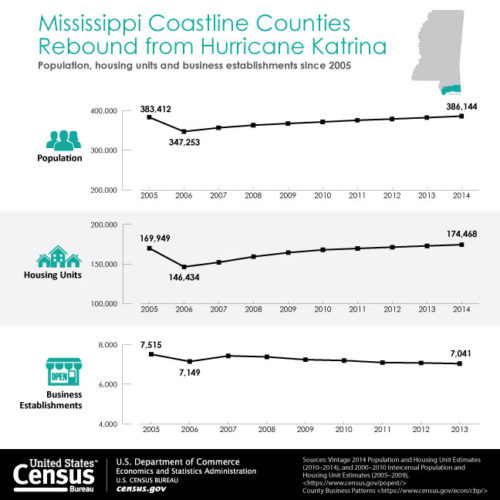

Today, about 2,700 more people live in Mississippi’s three coastal counties than before the storm and there are more housing units, according to a U.S. Census Bureau report. Slightly more African-American, Hispanic and Asian people live in those counties and the number of white residents has dropped by 4.7 percent. There are about 5,000 fewer businesses and employment is down slightly than in 2005.

Much has been made of the New Orleans’ 10-year recovery – it recently made the list of the 50 fastest-growing U.S. cities, with one quarter of its population having moved there since Katrina. However, while there has been what The New Orleans Index at Ten, a report by New Orleans-based The Data Center, calls “economic and reform-driven progress,” the poverty rate in New Orleans has risen to pre-Katrina rates and is now a “crushingly high” 27 percent. The U.S. poverty rate is 14.5 percent.

In metropolitan New Orleans, employment and income disparities between African-Americans and white are “starker than national disparities,” according to the report. Poverty is increasing in the parishes surrounding as well.

The city is also whiter, with 7.5 percent fewer African-Americans and 4.7 percent more whites, according the Census Bureau. African-American residents still remain New Orleans’ largest race or ethnicity at 59.8 percent, the report said.

The city is also whiter, with 7.5 percent fewer African-Americans and 4.7 percent more whites, according the Census Bureau. African-American residents still remain New Orleans’ largest race or ethnicity at 59.8 percent, the report said.

Racial divisions and inequalities the storm revealed continue to trouble the city. Ten years after Katrina, white and black New Orleanians have drastically different opinions of the city’s recovery, according to a survey by the Public Policy Research Lab at Louisiana State University that was released Aug. 24. Almost four in five white residents (78 percent) say that Louisiana has “mostly recovered,” while nearly three in five African-American residents (59 percent) say it has “mostly not recovered,” the survey said.

It is against this backdrop that The Episcopal Church’s ministry goes on every day across the region.

Over the course of 10 years of recovery thus far, “we’ve learned a lot of lessons about the immediate needs” and how those needs change over time, Louisiana’s Bishop Thompson said. “That’s a gift that the people in the Gulf can give to the church,” he suggested.

Thompson’s counterpart in Mississippi, Bishop Brian Seage, who became diocesan bishop earlier this year, said in an Aug. 26 video message to the diocese that “out of death brought by Katrina began the resurrection of the coast.”

Rob Radtke, who had just begun work as Episcopal Relief & Development’s president when Katrina hit and who went to Louisiana soon after, said the way the organization works in 2015 is “deeply informed by the experience of responding to Katrina.”

While other denominations had “very well-thought-out” response plans in 2005, “The Episcopal Church had not then really thought about what its role would be in times of disaster,” he told ENS. When he was hired, Radtke had been charged with developing a strategic plan for the organization and Katrina made it very clear that Episcopal Relief & Development had to develop a “serious U.S. disaster response program,” he said.

(A series of blog posts about Episcopal Relief & Development’s Katrina response is here.)

Today, the organization does not have a “one size fits all style” of response and it does not have the “boots on the ground” response practiced by other denominations, said Radtke. Instead, it uses an asset-based community development model to discern and help strengthen dioceses’ capacities “so that in times of disaster, they are leveraging their strengths to respond to the needs that are presented to them.”

After a disaster, people often turn first to houses of worship for help and solace. “The Episcopal Church needs to embrace that reality,” Radtke said. “It’s a huge opportunity for ministry,” he added, and one upon which Episcopal Relief & Development’s U.S. Disaster Program is founded.

That program continues to partner with the diocese of Louisiana, Mississippi and The Central Gulf Coast, according to Abagail Nelson, Episcopal Relief & Development senior vice president for programs. Deacons from the area deacons have shared their experiences in disaster response with others around the country via the organization’s Partners in Response program, Nelson added.

In addition to being in touch with Episcopalians ahead of predictable potential disasters, the organization strives to focus quickly on strengthening local congregations’ response by listening “with open ears and hearts to what do the local parishes feel called to do,” Radtke said.

And, in Louisiana and Mississippi, local congregations responded almost immediately and, 10 years later, many of their ministries have changed and continue. Here are some examples.

St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Gulfport, Mississippi

After Katrina, this 169-year-old congregation’s first response was to gather for worship and to start to rebuild a community that had been devastated by the hurricane. On the Sunday after Katrina had torn their church from its gulf-side moorings, parishioners gathered on the remaining concrete slab. The Rev. James “Bo” Roberts, then the rector, tearfully asked the survivors to remember their white wooden church with its steeple and green shutters.

“St. Mark’s is gone if that’s what you think it is,” he then told them. “But if you think it’s you and me and the rest of us, then we will build on from here.”

With Roberts’ prompting, the members took a daring and long step off the beach after the storm.

Now located a few miles inland and north of its historic site, St. Mark’s sits in the middle of five neighborhoods. Many new young families have joined the church. Vacation Bible School this summer had to be split into two groups because so many children participated. Ministry to children and youth is a new characteristic of St. Mark’s these days, the Rev. Stephen Kidd, priest-in-charge, said.

Kidd also noted that the transformation isn’t limited to St. Mark’s. All of the clergy in the Mississippi Gulf Coast churches are new in the last five years or less and most of them are in their thirties and forties, he said. They and their congregations are transforming their ministries, in one place turning their surviving parish hall into a feeding location for homeless people and in another instance collaborating on youth ministry.

“We all are sharing in this interesting experience of being clergy at churches who have all experienced this trauma, but have also risen out of that in a variety of new and interesting ways,” he told ENS. “So it really does feel like we’ve been co-opted into a resurrection story that started before we got here.”

All Souls Episcopal Church and Community Center, New Orleans

New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward was swamped by anywhere from four to 20 feet of water when the Industrial Canal’s walls failed after Katrina made landfall. A month after Katrina, Hurricane Rita flooded the neighborhood again.

It was in this community that the Diocese of Louisiana and the Church of the Annunciation (see below) launched what was then known as Church of All Souls as a mission station to minister to the many families who were trying to return to their homes. The congregation began in the garage of a parishioner during a time when few homes on the street were occupied. The congregation then rented space at a nearby Baptist church. Now housed in a former Walgreens drug store, All Souls was named in honor of the new souls who would come to worship and those souls who were lost in Katrina’s waters.

Then-Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams blessed the Walgreens building while he was in the city for the September 2007 meeting of The Episcopal Church’s House of Bishops. Williams said that the planting of All Souls showed that “when other people are running away, we as Christians ought not to run away; we ought to be there.”

One day earlier this year, six young children came bouncing their basketball past the church while Happy H.X. Johnson, director of the community center, stood talking to a reporter. He went back inside the building to get pre-made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and boxes of chocolate milk for them.

“We are working very hard to cultivate the next generation of leaders in the Lower Ninth Ward,” Johnson said. “We’ve got a lot of work to do and that work is almost never over but we take it seriously.”

The community center provides a free after-school program with volunteer tutors. “We feel very blessed and fortunate to be entrusted with this mission to educate God’s children,” he said. “It’s a very rewarding experience.”

Every day, Johnson said, All Souls lives the gospel imperative to serve the least among the community’s members. “We’re doing some of the most important work the church could be doing in an area that experienced extreme flooding, extreme devastation,” he said.

After Katrina some politicians and others said the Lower Ninth should be bulldozed and made into green space. “This is more than green space. This is centuries-old home ownership, thriving educators, dynamic musicians like Fats Domino whose house is right down the street,” Johnson said. “So this is a place with a lot of meaning and a lot of history, and it’s just great that The Episcopal Church is here doing this work.”

Christ Church Cathedral, New Orleans

Just before Katrina, Christ Church’s dean, the Very Rev. David duPlantier, was new to his post and a study had shown that the congregation on St. Charles Avenue in the Garden District wanted to find a way to connect with the Central City portion of its neighborhood. Central City was a center of African-American commerce and culture in the first half of the 20th century. It later fell into decline after the city integrated. It is said to have the highest percentage of both homicides and churches in the city.

Katrina has put that desire for congregational connection into action to the point where duPlantier said the cathedral’s rooms are so blessed filled with community group meetings that it’s hard sometimes to find space for the vestry.

“We’re just at the beginning of it but it’s really brought people into the cathedral – hundreds, maybe thousands of people in the last 10 years,” he said. “We’ve made ourselves not only a part of the neighborhood but a central part of the neighborhood that we’ve been in for 120 years.”

DuPlantier called the transformation the “logical extension of what a cathedral at its best is.”

After beginning as a diocesan ministry with strong backing from Episcopal Relief & Development, Jericho Road Episcopal Housing Initiative has become a ministry of the cathedral. It has also expanded its view of its mission from simply house building to helping residents build communities in a city known for its neighborhoods. An earlier video from ENS’ Katrina 10 years later coverage tells the story of Jericho Road’s evolution.

Church of the Annunciation, New Orleans

Three weeks after Katrina, after the water had been pumped out of the city’s Broadmoor neighborhood and thus out of the Church of the Annunciation, there were still tree branches strewn among the jumbled pews that the floodwaters had floated. There was evidence that looters had been in the buildings and all the recent renovations to its school wing were for naught, said Noel Prentiss, the church’s sexton.

But the church’s first concern about cleaning up was to make it possible to aid area residents. In fact, the church parking lot soon became the center of the neighborhood’s recovery.

The work began out of some tent canopies and a shipping container in the church’s parking lot. Those were replaced by two mobile homes; a doublewide that served as worship space and a singlewide was an office for the church and the neighborhood organization. Eventually the parish hall was cleaned out enough to be used as a warehouse for all the supplies the relief effort was accumulating, Prentiss explained.

It was three years until the congregation moved back into its sanctuary.

Early on the congregation expanded its ministry to host and house volunteer groups who were coming from all over the country to help. At it fullest, the Annunciation dormitory had 100 beds in which about 1,500 people slept annually. In the last 10 years, volunteers out of Annunciation rebuilt 110 homes in the neighborhood, according to the Rev. Duane Nettles, the church’s rector.

In summer of 2014, the dormitory went to 35 beds and the congregation has welcomed between 500-600 people annually as they come to do Katrina-related work. In all about 14,500 volunteers to date have stayed at Annunciation. This year the accumulated value of their labor will hit the $10 million mark.

“For us, we see that part of our call coming out of this is to remind people that small Episcopal churches can do really mighty things,” Nettles said. Especially, he added, those congregations that adopted the ancient model of a cathedral being the center of a community’s life.

Another reason for hosting volunteers is to help other Episcopalians learn about the power of mission. This summer when a group of youth volunteers from the Episcopal Church in South Carolina stays at Annunciation, the parish will waive the nominal fee it charges volunteers to make the youth trip possible.

“We’ve seen the way mission has transformed our congregation and, time and time again, given it a new lease on life,” he said, adding that mission has also “in a really wonderful way caused holy hell” for congregations whose members volunteered in New Orleans and then went home to see what could be done in their communities.

“The best way to rebuild yourself is to get out there and get beyond yourself,” Nettles said.

St. Anna’s Episcopal Church, New Orleans

St. Anna’s Episcopal Church, in the neighborhood just north of the French Quarter, has a large board tacked up on the exterior wall near the church’s name. Called the Murder Board, it is a list of every murder in the city dating to 2007. It witnesses to the individuals who make up the statistics of the city’s murder rate while the congregation ministers to the living.

After Katrina, according to the Rev. Bill Terry, St. Anna’s rector, the parish got so many offers of help from elsewhere in The Episcopal Church, that the leaders eventually invited representatives of the 12 congregations that seemed the most engaged to come to New Orleans. St. Anna’s Medical Mission grew out of those conversations.

The recreational vehicle-based mobile clinic traveled all over the greater New Orleans area offering medical care during a time when there was little other care available. Luigi Mandile, currently the parish administrator, piloted the van in those early days, “driving around ruins and trees and houses and boats.” After a day of listening to people’s experiences of Katrina and its aftermath, Mandile would go home and cry, but those days “strengthened me,” he said.

These days the medical mission focuses on residents who don’t have health insurance or who can’t afford their deductibles and co-pays, and those without a routine source of healthcare. The need, while different than that right after Katrina, is crucial.

Life expectancy is 20 years less than communities two miles away from the Treme/Seventh Ward/Lafitte neighborhoods in which St. Anna’s sits. There is a high rate of disease and death related to cardiovascular issues, stroke and diabetes, and residents frequently use hospital emergency rooms both for non-emergency issues and for help in managing chronic diseases.

But even then, people tend to go to an emergency room only when they are very ill. There is a historic, cultural tendency, not to seek treatment outside the neighborhood that is complicated by lack of knowledge about existing medical resources and a lack of transportation, according to Terry. The city’s traditional charity hospital system has meant that some New Orleanians have never had to enroll in an insurance plan and choose a regular doctor.

Those attitudes have to change “and we’re working to change it, but it’s going to take time,” said Diana Meyers, St. Anna’s community wellness director.

The parish’s other post-Katrina ministry, Anna’s Arts for Kids, has grown to the point where it has a certified teacher as its leader and volunteer tutors come from Tulane and Loyola universities.

“So this isn’t just a bunch of nice people saying ‘let’s read a book together,’” Terry said. “These are professional, educated, motivated people who are filling the gaps” in the education system in that part of town.

The program has also fueled another challenging phenomenon.

“Here’s my dilemma: we now have 30 children ranging in age from toddler to very early adolescents. Out of the 30 children, half don’t have parents here,” Terry said. “There’s no formula” for how to minister to a group of children aged four to nine years who come without a parent’s consent. Most of their parents are drug addicts or incarcerated, but these children, some of whom have been in the after-school program, show up, often wearing pressed shirts and bow ties.

They come, Terry said, because St. Anna’s is “the safe place for them … it’s the place where they get some love. They get comfortable, they’re engaged, they’re spoken to.” They attend Sunday school and they partake of the buffet that is spread after Mass.

“Those little guys swarm over it like ants on candy and that upsets some people,” Terry acknowledged. But, the children’s presence is another “post-Katrina phenomena and part of the ministry that we’re doing now. A dozen kids show up at this church, uninvited, to be here and worship here, to be with us, to be safe, to be fed,” he said. And they’re telling other children in the neighborhood that they ought to come, too.

St. Anna’s has even bigger plans for its community ministry. In 2010 the parish bought the historic Marsoudet-Dodwell House on Esplanade Avenue two blocks down from the church. Built in 1846, the house that was owned by Eliza Ducros Marsoudet, a Creole woman, was recently included in the 2015 New Orleans’ Nine list of the city’s most endangered sites.

The home, which includes slave quarters now called “the Dependency” and partially rented out as an apartment, was filled with junk when St. Anna’s took ownership. It was missing parts of its floors and needed structural stabilizing. However, the interior is filled with historic features such an upstairs room whose walls are made of “barge board,” old-growth timber no doubt cut in the upper Midwest and turned into barges that floated goods to New Orleans. Rather than haul the barges back upriver, they were typically broken apart and used in home building.

There is still much work to be done before the parish’s vision of a community center with “a focus on arts and culture that harnesses the youthful energy and talents of the next generation,” according to the website devoted to the project.

The Dragon Café at St. George’s Episcopal Church, New Orleans

The December after Katrina when New Orleanians were filtering back into the devastated city, the Garden District and Uptown sections of town were “still a frontier town,” according to parishioner Tom Forbes, a maritime lawyer. “There was nothing after six o’clock. There was one supermarket. It was dark at night; you’d drive up dark streets. There was maybe one restaurant open … you could score lunch off a Red Cross truck, but it was hard to get dinner.”

Forbes recalled that then-Bishop Charles Jenkins suggested that Christ Church Cathedral, a mile west on St. Charles Avenue from St. George’s, ought to serve as a clothing exchange (for weeks the front lawn was lined with clothing racks, shoes and cleaning supplies), Trinity Episcopal Church, with its large clergy staff, could be a counseling center and St. George’s, which had a history of feeding people during Carnival as a fundraiser, would be the feeding church.

“Initially it was part of our intention to feed our own parishioners and anybody else who walked in,” said Forbes, who still serves food at the café. “And gradually over the years the parishioners got fixed up spiritually and ‘housing-ly,’ but by then we’d begun to gather a crowd of people who were under-housed or literally from the street, and volunteers – the out-of-state volunteers who came here and literally saved this town.”

At what is still known as the Dragon Café, the initial Friday night meals began with donated food, including three freezers worth of food from at least one Mississippi cruise ship that went into dock early because it had no business, according to Forbes. Soon the café began serving on Thursday nights as well, often with live music and what Forbes calls “real fellowship, commiseration, gratitude, and faith.”

As the Garden District came back to life and the café realized its mission was changing, the parish switched from dinner to Sunday breakfast to better serve the clientele it was attracting. The Rev. Richard B. Easterling, St. George’s rector, said the café staff also realized that a lot of other agencies were serving hot food in the evenings.

“What makes our ministry cool is that it is parish-led,” Kelly McAuliffe, the café’s volunteer coordinator, said. “It’s regular folks who work 9-to-5 jobs who get up a little earlier on Sunday and they serve.”

Recalling one of the traditional post-communion prayers, McAuliffe said, “This is the work God has given St. George’s to do.”

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, New Orleans, Homecoming Center

Hurricane Katrina transformed people as well as the physical landscape of the Gulf. Connie Uddo says she is a good example.

When Uddo and her family moved back into the Lakeview section of New Orleans in January 2006, they were just one of 10 families living on streets that used to have 8,000 occupied homes. Katrina’s floodwaters destroyed the two lower units of the triplex they owned.

“There were no insects, there were no birds,” no street lights, no mail or newspaper delivery “for a solid year,” she said. Looting was still going on; their car was broken into. It was depressing, and Uddo, who was a tennis professional before Katrina but was then without a job, wasn’t sure she could continue to live there.

“I just got face down to the Lord and said ‘Give me a word; show me how to live here,’” she said. Then Uddo came across a verse in 2 Chronicles advising strength and courage with God at one’s side in the face of adversity.

She decided to open up her house as a recovery center. She and others began cleaning up their neighborhood. Uddo went to a rebuilding workshop at St. Dominic’s Roman Catholic Church across the street from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church where St. Paul’s then-rector, the Rev. Will Hood, introduced himself after Uddo had explained her work. He invited her to move her operation into a building behind St. Paul’s. She, Hood, the parish and the diocese’s Office of Disaster Recovery began St. Paul’s Homecoming Center, which Uddo said became Lakeview’s recovery hub.

As of December 2013, the center estimates it had touched the lives of more than 100,000 people and coordinated more than 60,000 volunteers, while also providing more than $200,000 to victims of hurricanes Sandy and Isaac.

The center moved to the neighboring Gentilly area about six or seven years ago, Uddo said, and “plugged in the model” of ministry begun in Lakeview, but adapted it to the fact that the neighborhood had been lived in longer after Katrina than when the center began in Lakeview. It was important to come in “very gently” and not presume to say that Lakeview folks were coming in to show Gentilly residents what to do, she said.

“We had to figure out a way to reinvent ourselves,” she said.

The Homecoming Center is now St. Paul’s Senior Center to serve elderly residents in both the Lakeview and Gentilly neighborhoods, many of whom are still dealing with issues from Katrina. Wrecked houses remain standing and inhabited homes are sparse on some streets.

The center provides meals, case-management services, activities ranging from bingo to computer classes, and depression and isolation prevention, and tries to foster “an active and engaging environment.” Uddo is the center’s development director.

The transformation of the center and, Uddo says, of her own heart has been hard. And, while she would not wish Katrina on anyone, “I thank God that he brought me through this storm because I am just a deeper, richer person, and I have my priorities straight.”

Editor’s note: This story is the last in a weeklong series stories and videos about the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina and The Episcopal Church’s role in the Gulf Coast’s ongoing recovery. Other videos and stories are here.

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is an editor/reporter for the Episcopal News Service.

Social Menu