Absalom Jones’ vibrancy lives on at St. Thomas, PhiladelphiaPosted Feb 13, 2014 |

|

In conjunction with Black History Month, the Episcopal News Service will publish feature articles on several historically black Episcopal congregations during February.

The congregation of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, Philadelphia, during the Palm Sunday procession in March 2013.

[Episcopal News Service] Feb. 13 may be the church calendar’s official recognition of the life and ministry of the Rev. Absalom Jones, but for Mary Sewell Smith and others at the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia, every day is founder’s day.

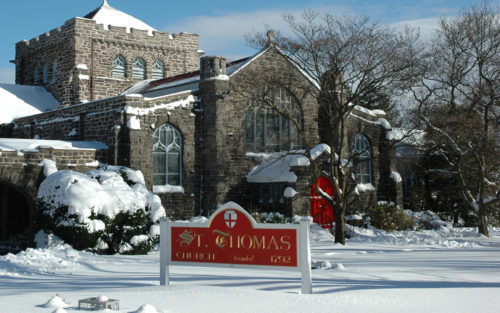

Jones – the Episcopal Church’s and the nation’s first black priest – founded St. Thomas in 1792 as the country’s first historically black church of any denomination, and “that spirit that permeated the early church has come down through the years and is still alive and well and thriving,” Smith said.

“A guiding force in our church is the life and legacy of Rev. Jones. It is just part of my life,” said Smith, a lifelong parishioner and current member of the church’s historical society. “We try to live up to the principles he espoused: freedom, liberty, education, worship, community service.”

Besides St. Thomas, 90-some historically black Episcopal churches remain today, congregations created by blacks not welcomed in mainline Episcopal churches post-slavery and during racial segregation throughout the United States, according to the Rev. Harold T. Lewis, a former staff officer for black ministries at the Episcopal Church Center in New York and the author of “Yet With a Steady Beat: the African American Struggle for Recognition in the Episcopal Church” (Trinity Press International, 1996).

The oldest, St. Thomas, grew out of the Free African Society, an independent mutual-aid organization created by Absalom Jones and Richard Allen to provide assistance for the economic, educational, social and spiritual needs of the African-American community. Those efforts continued in the church.

“Most black congregations have always been about uplift, social action, outreach and empowering the community,” Lewis said.

“What is unfortunate is that many people in the church, black and white, are unaware of that history and don’t know how many people have fought to get us where we are today,” he added, citing the Episcopal Church’s checkered past with regard to African Americans and racism.

Infused by the spirit of Absalom Jones

One of Smith’s earliest memories is of gazing up at the iconic portrait of Jones painted by Raphaelle Peale in 1810 and hanging in the church narthex as her father told her the story of St. Thomas’ founder, who was born into slavery, taught himself to read and purchased his freedom in 1784. Six years earlier, he had purchased his wife Mary’s freedom.

Jones served as a lay minister until he and other blacks were asked to leave St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. That exodus prompted Richard Allen and Jones to create the Free African Society. It led to Allen founding the African Methodist Episcopal Church and to Jones’ ordination in the Episcopal Church as a deacon and, nine years later, at age 58, a priest.

But then-Pennsylvania Bishop William White would agree to ordain Jones and receive St. Thomas into the diocese only if the church did not send any clergy or deputies to diocesan convention, thus depriving blacks of voice or vote in church governance, which “characterized the duality of race relations within the church for much of its history,” according to historical documents of the church.

Smith recalled visits to Jones’ grave, located “in the same cemetery where our family graves are. And when we would go to visit our family, we would always say a prayer at Rev. Jones’ marker.” Jones’ remains have been exhumed since then and cremated and placed in an urn at a commemorative chapel inside the Gothic-style church, she said.

Smith grew up playing on the church steps, along with childhood friends Mercedes Sadler and sisters Lucille and Isabel Hamill. The 70- and 80-something women continue to share a love of church and history as members of the historical society. They say the church infused them with a sense of belonging. Its story is their story, and also the nation’s story.

History lives: ‘Very much a part of church’

One of the greatest joys for retired schoolteachers and sisters Isabel Hamill, 87, and Lucille Hamill, 83, was finding a mention of their aunt, Bertha Jones, included among the names of church women supporting various war efforts.

“There were notes about the women who helped roll bandages for the Spanish-American War,” said Lucille Hamill. “And the women held canteens during World War I and World War II, where the young men could come and eat and be mothered by the older women in the church, and they used to come.”

For the Hamills, finding words for all that the church has meant to them is difficult. “It made you feel included, in a city where there was still rampant segregation when we were young,” Lucille Hamill said. “It just made you feel a part of something bigger than yourself, and that was important.”

To preserve the congregation’s history, the church had created an archive in an adjoining building but encountered climate and moisture issues that are being resolved, Smith said. The church’s archives offer a window into a past filled with social activism and community outreach, and even a glimpse of future possibilities.

“I think because we know quite a bit about what the church has been like down through the years, it leads us, it infuses the present,” Smith said.

Included in the archives are Jones’ baptismal records from the late 1700s, birth and death records, sermons and speeches, membership rolls and vestry meeting minutes.

Some documents, in the process of being restored, predate the church. “We actually have a volume of accounts from the Free African Society,” Smith said. “Everything that I ever read says that no records of this organization had survived, but, in going through our old records, we have come across this volume, from 1790 until 1792, when the society disbanded and transitioned into the church.

“Each member had a page, and it shows they paid a couple of shillings, and this was money used to serve the poor and the disabled. You can see how people paid their dues and how they would miss a couple of months and then catch it up.”

Looking back, the focus was “always on community service,” she said. “The St. Mary’s Guild in the 1800s made clothing for children who couldn’t afford clothes to go to school. The Sons of St. Thomas – we have the minutes of these organizations – fashioned themselves after the Free African Society and functioned very much the same way.”

The Dorcas Society was composed of women, “and their primary function seems to have been to arrange and pay for burials of women in the church or community,” she said.

Church membership rolls read like a who’s who in African-American society, said Mercedes Sadler, 77, a sixth-generation Episcopalian and a member of the chancel choir, one of five church choirs.

They include James Forten, born in 1766 to free black parents. He fought in the Revolutionary War and parlayed an apprenticeship at a sail-making company into a wealthy business venture. He used more than half his wealth to purchase freedom for slaves, to help finance William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, to operate an Underground Railroad station out of his home and to fund a school for black children.

Octavius Valentine Catto was “a Renaissance man and a St. Thomas vestry member back in the day,” Sadler said. “He was shot and killed while trying to get people to go out and vote.”

Catto was about 5 when his family moved to Philadelphia from South Carolina in 1850. A social activist, he was also an accomplished baseball shortstop and player-coach and the founder and captain of the Pythian Baseball Club. A Republican and supporter of Abraham Lincoln, he worked for passage of the 15th Amendment, allowing black men the right to vote, but was killed on Oct. 10, 1871, Election Day. One of his baseball bats is among the archive memorabilia.

St. Thomas’ clergy and parishioners played key roles in the abolition/anti-slavery/Underground Railroad movements and the early equal rights movement of the 1800s, according to the website. “Over the past 50 years, St. Thomas has figured prominently in the civil rights movement, the NAACP, Union of Black Episcopalians, Opportunities Industrialization Center, Philadelphia Interfaith Action and the Episcopal Church Women.”

For Smith, the memories are personal and precious. She recalled watching her brother practicing altar duties and the art of candle-lighting at home. Although girls were not allowed to serve as acolytes then, she discovered other ways to serve, as did her mother.

“My mother was what you call an acolyte mother,” Smith said. “In those days, you never knew which acolytes would show up. So, if a short one showed up, she had to pluck up the cassocks and put pins in them. I used to be in the sacristy with her before the service, getting them ready. In those days they didn’t have girls as acolytes, but I always found things to do.”

Looking back, moving forward

Besides community involvement, St. Thomas has remained committed “to uphold the knowledge and value of the black presence in the Episcopal Church,” according to the website. The church is offering a Black History Month exhibit, conducts regular tours for visitors and continues to preserve its wealth of records and to develop its archives.

“It’s such a blessing that we have these wonderful records,” Smith said. “Somehow, it was recognized, down through the years, that these records were valuable. You really get a sense of what life was like, the people, who were the movers and shakers. It has connected me and expanded my knowledge of black history and connection to the black community in a way I didn’t have.”

Although the church has moved four times since Absalom Jones founded it, it continues to grow and welcome others “with a little bit of something for everyone,” Sadler says. Its members represent the range of the African diaspora as well as “a fair number” of whites.

Stained-glass windows installed in 2000 pay homage not only to Jones but also to several black giants of the faith: Archbishop Desmond Tutu; retired Massachusetts Suffragan Bishop Barbara Harris, the first woman elected a bishop in the Episcopal Church; and Bishop Suffragan Franklin Turner, who bequeathed a crosier to the archives.

Turner, who retired in 2000, died Dec. 31, 2013, and a requiem was held Jan. 11.

At a 1992 service at St. Thomas to rebury the remains of Absalom Jones, Franklin had said of black Episcopalians, “We have indeed come this far by faith.”

“We can be justly proud of our sojourn in the Episcopal Church, although it has been an uphill struggle,” he said.

Uplift, empower, welcome

In the spirit of Absalom Jones’ push for education, the church is launching an after-school program, said the Rev. Angelo Wildgoose, associate rector.

“The after-school program is geared toward schools in our area and is basically looking towards helping with homework, technology, computer sciences, with SAT tips; and the church is involved in a variety of outreach efforts,” he told ENS.

Among other church programs, the five choirs offer a range of music: classical, spirituals, gospel, jazz.

A new middle school and high school “Souldiers for Christ” class is set to begin Feb. 16, said Wildgoose, who has served at the church since December. Another program, designed to connect students with local Episcopal churches during their college years, re-launched in December with about 15 students, he said.

“The idea is to give them that home away from home where they’ll be able to continue to worship at an Episcopal church and at the same time to have some familiar surroundings,” he said. “We’re trying to make sure we keep our young people engaged, from the children up to those in college. We’re stressing a lot of parental involvement.”

Average Sunday attendance is about 400 at one service, with about 50 children in the church school. “There’s a little bit of something for everyone here,” Sadler said.

For Smith, her lifelong friends and many others, St. Thomas has been a spiritual and a palpable home, “an anchor, somewhere to organize their life around, and with people of like interests,” Smith said. “We’re fortunate that our congregation is multi-generational, with a wonderful church school, a great group of teens and all the ‘Souldiers for Christ,’ and that each age group can feel ownership in the church and become an active part of the life of the church.

“It has certainly added to my life, and I think that’s what people find when they come here, and that’s why every Sunday we have people joining the church.”

— The Rev. Pat McCaughan is an Episcopal News Service correspondent.

Social Menu