Churches stand up for lives lost, take stand against violencePosted Jan 23, 2012 |

|

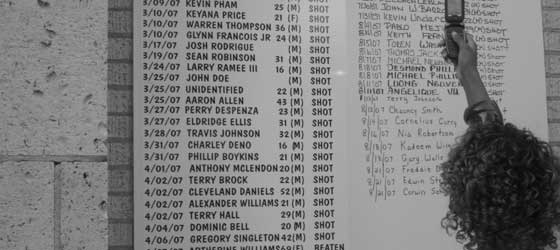

[Episcopal News Service] A few weeks into 2012, the Rev. Bill Terry already had at least 20 additions for the “Murder Board” outside St. Anna’s Episcopal Church, near New Orleans’ French Quarter, including:

- Jan. 6, Keian Ester, 11, shot

- Jan. 7, Michael Johnson, 21, shot

- Jan. 7, Eric Robinson, 41, shot/burned

- Jan. 8, Joseph Elliot, 17, shot

- Jan. 10, Tiffany Frey, 36, shot

- Jan. 10, Lamar Ellis, 21, shot

- Jan. 12, Keishuane Keppard, 20, shot

- Jan. 17, Gerald Barnes Jr., 21, shot

- Jan. 18, unidentified male, shot

“We’re less than a month into the year and we’re already averaging a murder victim a day,” Terry said. “Last week we had a young man who was gay who was shot and then burned. It’s a holocaust. It’s a national travesty.”

The church created the board in 2007 after public outrage over several particularly violent deaths subsided “and nothing changed,” said Terry, rector.

Anchored in front of the church the 4 x 8-foot white coroplast sign has sought to raise public awareness and to challenge the anonymity of urban violence, Terry said during a Jan. 19 interview from his office.

“We tend to talk in terms of numbers, the murder rate, how many murders. It has a dehumanizing quality and we’re in the business of humanity.”

Each week, he climbs a ladder and adds new names. The board intends to ask the same question a victim’s mother once asked Terry: “Why did my baby have to die?”

“I made a promise to her and the rest of the mothers of victims of violence that we would not stop doing this, that somebody does care,” he said.

Across the country, from Chicago to Georgia, New Orleans to Alaska, Episcopalians are seeking to raise public awareness about violent deaths to lend a voice to those who can no longer speak for themselves, and to offer hope to loved ones living through its aftermath.

Volunteers at Holy Innocents Episcopal Church in Sandy Springs, Georgia, about 15 miles north of Atlanta, held an all-night vigil Jan. 21 for the community’s children, some 550 in all, who died violently in 2011.

“Believe it or not, those numbers are down from the previous year, when we read about 800 names of dead children. That number was staggering to us,” said the Rev. Allison Schultz, assistant rector, in a recent telephone interview.

The vigil ended at 7 a.m. Jan. 22; about 100 community members attended a 4 p.m. requiem mass for the victims the same day. The goal, said Schultz, is to create public awareness about the plight of “the holy innocents of our day” killed by abuse and other violence.

“Children are particularly vulnerable to violence, especially under age four. They can be hidden away, it’s difficult for them to speak up,” she added.

The names of young victims–and this year, because of recently-enacted state privacy laws, only their initials—are read aloud during vigils and recorded in a book kept at a prayer station inside a church beside an icon of the holy innocents, she said.

“The scene is somewhere between Bethlehem and Egypt; Mary is on a donkey, Joseph is walking beside her and babes-in-arms are being carried to heaven by angels,” she said.

This marks the second year of an effort Holy Innocents aims to make an annual event, offered as a response to the violence, Schultz said.

“As Christians, how do we respond to such violence? By trying to be as nonviolent as we can in our communication, in our action, our work,” Schultz said. “It’s just about the power of prayer and then also claiming that those lives might be lost to us but that they live on in resurrected life. They’re not just lives lost — they now have a home, a place where they rest in peace.”

Donations were given to the Drake House, a local center for women and children who have experienced violence, she said. Schultz added, “What we can do as church is to pray, worship and remember. It’s our job to hold that out for people to see what God might be calling them to do. The first step in anything we do as Christians is to see how God might be calling us to behave, to act differently.”

According to the Children’s Defense Fund, a private nonprofit agency founded in 1973 to advocate for the nation’s children, the United States ranks last among industrialized countries in protecting its children against gun violence.

CDF statistics for 2010, based on a 180-day school year, indicated that in the United States, a child or teenager is killed every three hours by a firearm, and a child is killed by abuse or neglect every six hours.

Bishop Jeffrey Lee remembers the 2008 killings of five students at Northern Illinois University in DeKalb, Illinois, and the wounding of 21 others by a lone gunman “as a searing event” during his first year as bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago.

“It reminded me that this violence is not isolated to urban cities. If it can happen in a place like DeKalb, Illinois, it can happen anywhere,” he said during a Jan. 21 telephone interview from Chicago.

He aims to launch “an ecumenical call to action” with a 4-mile march on April 2, Monday in Holy Week, to give voice to the more than 260 Chicago children murdered since 2008 and to offer hope in a city where many have tuned out as a way of coping.

“This is about class, about poverty, about race, about so many things so huge … it ought to outrage us, but instead it’s a small story on page eight of the Chicago Tribune,” he said. “I would like to change that. Every child who dies is our child. This is at the heart of our baptismal vows, to respect the dignity of every human being.”

He also aims “to equip people with tools to do something about it, neighborhood to neighborhood, as an ongoing initiative … a kind of companion relationship,” he added. The marchers will begin at the diocesan center and conclude at the John H. Stroger, Jr., Hospital, a trauma center which treats many victims of violence.

The Rev. Carol Reese serves as violence prevention coordinator at Stroger Hospital on the city’s near west side, where “some of the kids that wind up in the trauma unit already have their burial clothes picked out.”

The hospital’s trauma center handles about 5,000 patient visits per year; about 40 percent of patients and their families exhibit symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), she said.

Those levels average “about five times higher than the general population in the United States” and are comparable to those of war-torn nations, Reese said during a Jan. 19 telephone interview from her home.

“I met with a woman whose brother had been shot while he was trying to get another young person to safety,” said Reese, a licensed social worker and priest. “He ended up in the intensive care unit. This same woman had lost another brother to gun violence six years earlier. She still lives across the street from where it happened. Her 13-year-old son goes to school near there. She told me, ‘I feel like I have PTSD,'” Reese recalled.

“The problem is, it’s not over with,” Reese added. “There is the ongoing stress of living in an environment where you have to worry about your safety, where you see people being beaten up and murdered repeatedly.”

She hopes the upcoming march will help “make some personal connections with people who have been impacted by this type of violence and also with people in the communities trying to work together to curb the violence and to help people live through the aftermath.

“In the same way we build relationships with companion dioceses in Sudan or Mexico or New Orleans, we have to figure out ways to companion some of these families and some of the organizations working to support them. And we have to sign up for the long haul because it takes a long time to build those relationships,” she said.

The good news is, there’s always hope, she added. “The thing people of faith bring is a sense of hopefulness. We know about despair and we know that there is hope and there’s always a way out of it.” They can make a difference, she said, “f we learn how to truly see each other and if we learn how to connect with each other and really treat each other with kindness and compassion, which also means addressing injustice when it arises.

In Fairbanks, Alaska, a yearly “Gathering of Remembrance” that began in 1994 as a memorial to a murdered University of Alaska co-ed has become a way to remember all unsolved murder victims, said the Rev. Scott Fisher, rector of St. Matthew’s Church.

The observance is held at various locations yearly in April. In 2011, participants gathered at St. Matthew’s, and read the names of 33 people, all associated with unsolved Interior Alaska murder cases, he said.

The victims ranged in age from an eight-year-old to elders. A single candle was lit as each person’s name was read. The annual service initially remembered Sophie Sergie, a 20-year-old Yup’ik woman who was murdered in a dormitory bathroom. “Her murder is still unsolved,” Fisher said.

Back in New Orleans, the St. Anna Church’s murder board has sparked at least two other ministries, a five-day per week mentoring and arts program for inner city children and the “rose ministry.”

Volunteers take a rose each week to the city council, the mayor’s office, the chief of police and the district attorney “one rose for every murder victim” as a reminder of those lives lost.

“We are trying to humanize them,” said Terry, who added that the church is fundraising for a permanent memorial for the latest victims of violence. Their names are dredged out of police and newspaper reports.

“It’s a burden we bear proudly,” he said. “Every Sunday we read every one of these names. And every week I see people walking along the sidewalk or driving by that stop and contemplate what it (the murder board) says.

“You never know the outcome of something like this,” Terry added. “A lot of people say, what good does it do, does it stop the murders? But one police officer broke into tears at the sight of the board. She is a police officer and she had no idea of the totality of the violence and death. When you see the names that has the power to transform people. She left, changed.”

–The Rev. Pat McCaughan is a correspondent for the Episcopal News Service. She is based in Los Angeles.

Social Menu