Women are joining the House of Bishops at unprecedented rateHard work, the Holy Spirit and larger culture’s influence are seen as the motivatorsPosted Jul 1, 2019 |

|

All the women bishops and bishops-elect who had received the church’s consent to their ordination and consecration who attended the March 12-15 House of Bishops meeting at Kanuga Conference and Retreat Center in Hendersonville, North Carolina, pose for a group photo. Since that meeting, three more women have been elected to the episcopate. Photo: Mary Frances Schjonberg/Episcopal News Service

[Episcopal News Service] The first day of June was a historic, if somewhat distracting, day in the life of The Episcopal Church.

The Rev. Kathryn McCrossen Ryan was consecrated bishop suffragan of the western region of the Diocese of Texas on June 1. Photo: Diocese of Texas

While the Rev. Kathryn McCrossen Ryan was being ordained and consecrated as a bishop suffragan in the Diocese of Texas, many people in attendance were surreptitiously checking on the outcomes of two bishop elections happening that day. In both cases, laity and clergy elected women: the Rev. Bonnie Perry in the Diocese of Michigan and the Rev. Lucinda Ashby in the Diocese of El Camino Real.

Perry and Ashby are the seventh and eighth bishops elected in The Episcopal Church this year, and the fifth and sixth women, the most ever elected in one year in the church’s history.

“What a day for the church; what a day for women,” recalled Bishop Todd Ousley, the head of church’s Office of Pastoral Development who shepherds diocesan bishop searches. He admitted he was one of those people checking his phone.

Thus far in 2019, in addition to the six women elected as diocesan or suffragan bishops, Episcopalians in two dioceses have elected men to be their diocesan bishops. Four of those eight bishops-elect, all women, identify as people of color. At least one more woman will be elected bishop this year, on July 26, when the Diocese of Montana chooses from a slate of three women.

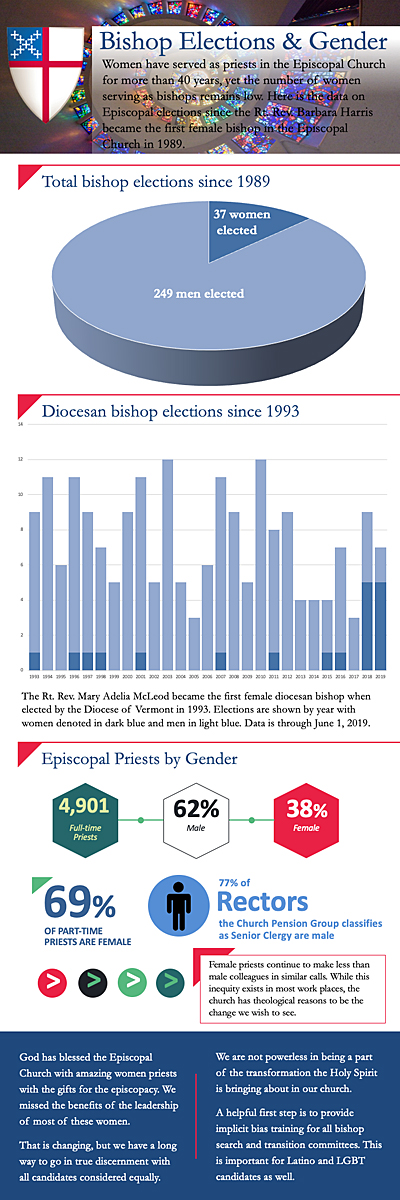

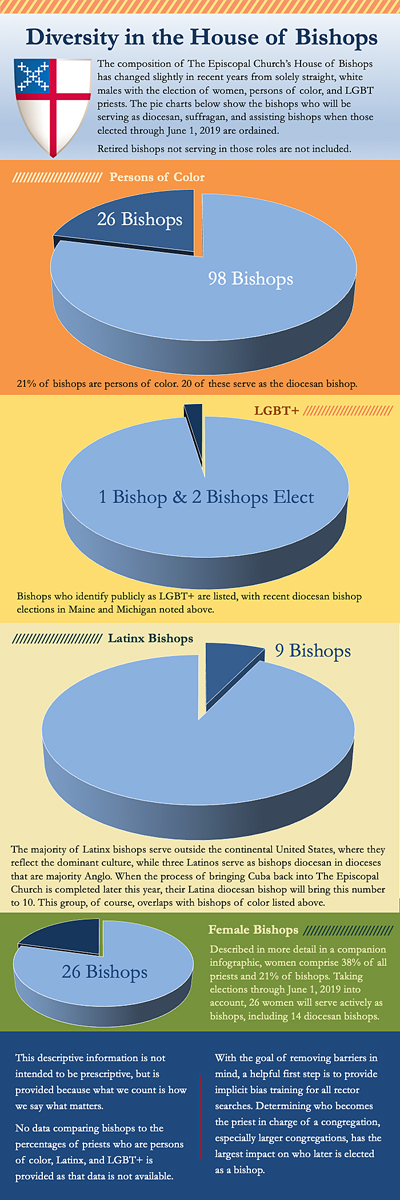

The Rev. Frank Logue, Diocese of Georgia canon to the ordinary, used data from a variety of sources for this graph and the two infographics below.

Diocese of El Camino Real Bishop Mary Gray-Reeves, a leading advocate for women discerning calls to the episcopate, has a two-fold reaction to the pattern of recent elections. “One is I’m elated,” she told Episcopal News Service. “Two, I recognize there is a tipping point happening.”

Merriam-Webster defines “tipping point” as “the critical point in a situation, process, or system beyond which a significant and often unstoppable effect or change takes place.”

Five more elections are set for this year. One woman is on the three-person slate in the Diocese of Taiwan’s Aug. 3 election. Two women are on the four-priest slate in the Diocese of Southern Virginia’s Sept. 21 election. The dioceses of Missouri, Oklahoma and Georgia have not yet announced their nominees.

Currently, 24 of the 127 active bishops (diocesan, suffragan, assistant or assisting) are women, according to statistics from Ousley’s office. They make up 18.9 percent of the total. If women and men elected but not yet ordained and consecrated are included, the count increases to 27 women bishops among 131 active bishops, or 20.6 percent.

Among the active bishops, there are 26 people of color (African American, Latino, Native American, Asian), accounting for 20.5 percent. Thirteen are African American men and five are African American women.

“As a female person of color, I have always seen the leadership in some of these women, so it is nice for the wider church to also embrace the leadership and the gifts of these women,” Zena Link, a member of Executive Council who also chairs the General Convention Task Force on Women, Truth and Reconciliation, told ENS.

The current House of Bishops roster, which includes retired bishops, is here.

What is prompting this trend?

Many observers credit the recent increase in the number of women elected as bishops to a confluence of societal and ecclesiastical trends, as well as years of active encouragement of women to consider an episcopal vocation. And, they all credit the persistence of the Holy Spirit.

“I feel like the church has always been right on the edge of wanting to do this but didn’t know how to do it and needed the right time to do it, and now is the time,” Link said. “I feel like it goes beyond the church right now.”

Ousley suggested that there has been what he called a dance between the larger culture’s changing attitude toward women as leaders and “the church’s efforts or, at certain points, the church’s resistance to making this shift.”

Ever since he was in seminary in the early 1990s, Ousley said, there have been equal numbers of men and women coming into the church’s ordained ranks. Yet, church leadership at all levels still does not reflect the demographics of the church. “I think the church has fumbled along at times in trying to figure out how we can begin to shift that,” he said, adding that there has been a “steady but slow gathering of interest and commitment to shifting the balance of power, if you want to use that kind of language.”

Now, he says, “the leadership in the church is clear that the balance must shift, and we’ve got to use everything that we can in our power to help make that happen.”

Bishops lament and confess the church’s role in sexual harassment, exploitation and abuse https://t.co/RdY1taSonN #GC79 pic.twitter.com/of4tDwaGKu

— Episcopal News Service (@episcopal_news) July 5, 2018

The voices and stories of women that played a significant role in the 79th General Convention are a recent example. A liturgy during which bishops confessed and lamented the church’s role in sexual harassment, exploitation and abuse included stories of both women’s and men’s experiences. The House of Bishops later adopted “A Working Covenant for the Practice of Equity and Justice for All in The Episcopal Church” that commits them to seek changes in their dioceses to combat abuse, harassment and exploitation.

Convention also approved a wide array of resolutions, many from the House of Deputies Special Committee on Sexual Harassment and Exploitation appointed by House of Deputies President the Rev. Gay Clark Jennings, ranging from clergy discipline, clergy compensation and pension equity for lay employees to gendered language and patterns of clergy employment.

Link’s committee is one of four General Convention called for in those resolutions. Another is tasked with developing model anti-sexual harassment policies, a third is studying sexism in the church and developing anti-sexism training materials and the fourth committee is developing a proposal for a churchwide paid family leave policy.

But, work behind the scenes has been going on for years. “There has been a concerted effort; this did not happen by accident,” the Rev. Helen Svoboda-Barber, administrator of the Facebook group Breaking the Episcopal Glass Ceiling, told ENS.

Svoboda-Barber and Gray-Reeves might well be two of those credited with helping the church reach this point. Gray-Reeves and a group of other senior female clergy leaders organized Beautiful Authority in 2011 to gather young female clergy for formation, support, networking and friendship.

The founders realized that such a group, which holds regular retreats, was needed because younger female priests “were asking the same questions that the first generation of ordained women were asking,” Gray-Reeves said. In terms of how women were experiencing and being experienced in ordained life, things had not changed very much in the then 34 years since women began being ordained as priest and bishops, she added.

The founders realized that such a group, which holds regular retreats, was needed because younger female priests “were asking the same questions that the first generation of ordained women were asking,” Gray-Reeves said. In terms of how women were experiencing and being experienced in ordained life, things had not changed very much in the then 34 years since women began being ordained as priest and bishops, she added.

Gray-Reeves explained that the younger women had to function as a minority in the church’s leadership structure, using coping skills they learned for survival in the system: the ability to listen well, to figure out how one fits into the system, to manage one’s affect in order to be heard.

“And yet, the very skills that we need to build the church today are the skills that people develop when they’re part of the nondominant group,” said Gray-Reeves, who in 2007 became El Camino Real’s third diocesan bishop and the church’s seventh female diocesan.

It took 10 days to fill the 20 places available for the first Beautiful Authority gathering. “We stumbled on a very serious need,” Gray-Reeves said.

At least four of the 20 attendees were ready to leave their jobs and leave ordained ministry all together, “and they didn’t because they made friends,” she said, noting that young women priests are still few and far between in the church. Some priests brought their newborn babies to the meeting.

Building on the success of that first gathering, Gray-Reeves went to her colleagues in the House of Bishops, seeking 15 bishops who would each donate $200. She soon had $4,000 and a conference center for the next gathering.

“The men understood that this needed to happen but that they couldn’t do it,” she said.

Gray-Reeves will soon leave El Camino Real to become the managing director of the church’s College for Bishops, which trains new bishops. Beautiful Authority is now led by Diocese of Virginia Bishop Suffragan Susan Goff and the Rev. Augusta Anderson, the canon to the ordinary for the Diocese of Western North Carolina.

Svoboda-Barber created Women Embodying Executive Leadership, or WEEL, a discernment program for Episcopal clergywomen, during which six to 12 women meet together for four three-day gatherings over up to two years to support one another. The members consider how God might be calling them to use their own leadership skills in the episcopate. Three groups have met thus far.

Research shows, Svoboda-Barber said, WEEL “enlivened all of those women to go back to their dioceses, to go back to their colleague groups and really talk more about the possibility of women being bishops.” They also set to work on getting women on bishop search committees and diocesan standing committees, she said. Between 30 and 40 women have participated in WEEL, but their influence has been greater than their number, Svoboda-Barber added.

Presiding Bishop Michael Curry stands with West Tennessee Bishop Phoebe Roaf at Roaf’s consecration May 4. Photo: Diocese of West Tennessee

She and others have also encouraged search committees to get training in implicit bias early in their processes, and to use techniques such as removing all identifying information and demographics from their first review of applicants’ materials. So-called “blind rounds” are “having a pretty profound effect on the search committees,” she said.

Svoboda-Barber is also an organizer of Leading Women, a joint effort of women in The Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada to explore a sense of being called to senior leadership position in both churches.

The election trend is not confined to The Episcopal Church. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, a full-communion partner, recently completed its spring assembly season during which regional synods elected eight women and five men as bishops. The Lutherans’ elections mean that there are now 23 female synod bishops plus ELCA Presiding Bishop Elizabeth Eaton in the denomination’s Conference of Bishops. The conference includes Eaton and one bishop each from the church’s 65 synods, along with and the ELCA secretary, thus meaning 36 percent of ELCA bishops are women.

Eaton is up for reelection during the ELCA’s Churchwide Assembly set for Aug. 5-10 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. That assembly will also consider a proposed social statement of women and justice called “Faith, Sexism, and Justice: A Lutheran Call to Action.”

“It’s definitely the year of the women,” the Rev. William O. Voss, the ELCA’s representative to The Episcopal Church’s Executive Council, told that group June 13. “We’ve had a number of women become bishops in the past but never the kinds of numbers that we’re see this year.”

Canonical barriers came down more than 40 years ago

There has been no canonical prohibition against women in The Episcopal Church’s episcopate since Jan. 1, 1977. That was the effective date of General Convention’s decision the previous Sept. 16 allowing women to become priests and bishops. (Women were eligible to become deaconesses since 1889 and deacons since 1970.) It took 12 years for the Rev. Barbara Harris to be elected bishop suffragan in the Diocese of Massachusetts, becoming the first woman bishop in the Anglican Communion.

An interactive timeline of the history of women’s ordination in the Anglican Communion is here.

Of the 286 bishops elected since 1989, 249 have been men and 37 have been women. Twenty women have been elected to head dioceses, beginning with Diocese of Vermont Bishop Mary Adelia McLeod in 1993, while 184 men were elected diocesan bishops.

In 2018, Kansas became the first diocese in the history of The Episcopal Church to offer electors an all-women slate. Svoboda-Barber was one of the three nominees. That year five women and five men were elected churchwide. Four of the women were chosen in October and November. The previous year saw three men and one woman elected.

The movement of the Holy Spirit in the recent elections is not to be missed. “I am thrilled with the diversity, not just gender, but also people of color and LGBTQ folks. It is thrilling to see. I believe the Holy Spirit is at work in this,” Svoboda-Barber said. “It’s not that women are better than men, but we will be better when our House of Bishops is more diversified. We’re going to be a better church when we are more diverse.”

I’m asked almost weekly if women are taking over the #Episcopal #HouseOfBishops. These charts show visually what we know intuitively—we have a long way to go before getting anywhere close. The goal is barrier removal. https://t.co/Gb4Jsx1H1x

— Jennifer Baskerville-Burrows (@JenniferBB) June 2, 2019

The Rev. Frank Logue, Diocese of Georgia canon to the ordinary and a nominee in the 2017 East Tennessee bishop election, told ENS, “The goal is to lower the barriers so that all candidates will be considered fairly and so that those the Holy Spirit is calling will be elected. When those God is calling find their way into our House of Bishops, I am quite sure it will more fully reflect the body of Christ in ways quite beyond gender. Then the question will no longer be whether someone is ‘electable,’ but whether the person is called by God to this diocese at this time.”

Ousley echoed the belief that the needed change needs to go beyond a demographic balance. “This is an issue of doing the right thing, the just thing, and also reflecting the fullness of the whole people of God,” he said. “That’s the deeper call.”

Logue, who compiled the data for the infographics in this story (some of which are updated versions of the ones Indianapolis Bishop Jennifer Baskerville-Burrows retweeted on June 2), predicted the changes he charted “will change the house in ways we can’t imagine.”

New bishops go through three years of training from the College for Bishops. Gray-Reeves will oversee that formation project in a context “radically different than it was 10 years ago,” she said. “What we have to offer will be different. The people with whom we will be working will be different. That requires significant consideration and change.”

“For instance, skills in adaptive change are going to be pretty critical,” she said. “I think we’re going to have some work around the biases piece because there is going to be bias.”

Link said she hopes that “these women will actually be able to lead without being micromanaged in their leadership. There’s a cultural tendency to challenge the authority of people of color. I’m not saying that happens in church, but I could see biases coming out possibly.”

For now, the new additions to the roster means the house “is going to look as if it’s changed,” Link said. “But with that needs to come some relinquishing of control, some openness, some willingness to support and [be] less likely to critique” and more willing to mentor.

“They’re there, but then what happens?” Link asked. “Will they be chairing committees? Will they be given the same opportunities? What will that look like exactly?”

– The Rev. Mary Frances Schjonberg is the Episcopal News Service’s senior editor and reporter.

Social Menu